Crackdown's cities are the real star of the series

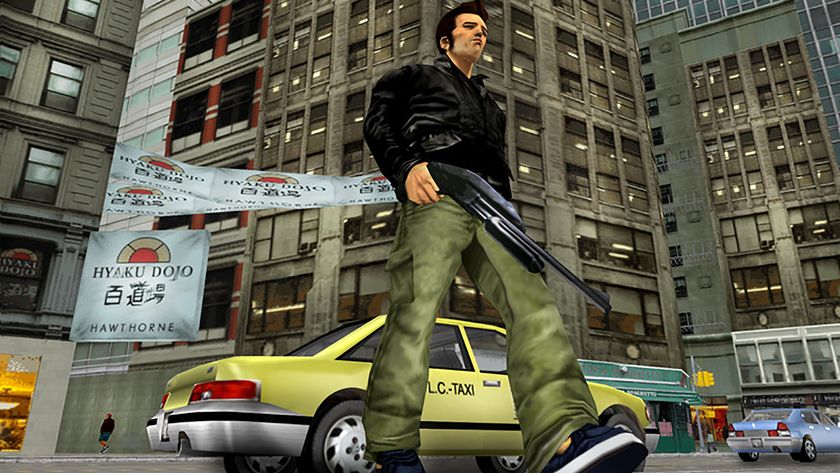

From the top of the Agency Tower you can see the whole thing: three islands of powdery textures and grimy neon, a battleground where game mechanics regularly pound story into the floor. You don’t come to Pacific City for the narrative, or for the limp set-pieces and other shreds of structure that hang upon it. You come here to jump around, to grab things and throw them, to explore and to level up your kicks while you do so. Crackdown’s more concerned with the moments than the arcs, and those moments are waiting on every street corner, whether you crave base jumping or base defending, car jacking or car tennis. And even though the upcoming Crackdown 3 is set in an entirely new city, that emphasis on experimenting in a giant, concrete and steel playground is set to continue. There's a lot to learn from the first two entries in the series.

Pacific City can be so ingeniously aimless that the first Crackdown was ruled, for the most part, by a treasure hunt: a mad dash for the Agility Orbs that the designers scattered across the rooftops only when they discovered that playtesters, raised on urban sandboxes where the heights of the buildings were mere indulgences, refused to look upwards. And yet between games, something changed: the sequel had the very same orbs but, the second time around, they didn’t have quite the same allure. For Crackdown 2, another, far more complex force guided players through the streets. What was it?

It still wasn’t story. The sequel’s handling of plot was little better than the original game’s, even if it did try to build the lurking anti-authoritarian sentiment into something a little sharper. It wasn’t the new missions, either, although the design team certainly had ambitions in this area, too. Quests that saw you jump-starting the derelict metropolis and clearing out a new breed of mutated freaks suggested that a serious attempt had been made to build encounters that deviated from the first game’s gloriously nonlinear hit-list. Such efforts were doomed to failure, however. This is, after all, a series that rejects traditional content like an unnecessary skin graft. Crackdown’s about geography, not structure, which explains why its best levels are neighbourhoods and its best set-pieces are buildings.

It may also help to explain why those glowing collectables had lost their starring role. In the hands of Realtime Worlds, Pacific City had been a brilliant place to explore if you stepped away from the plot: the fun of the game was following that chain of orbs until you’d visited every borough and climbed every chimney. With a brutal production schedule, Ruffian couldn’t hope to match that kind of intricacy. Without the time to build an entirely new playground, it took an unusual risk. It went back to the original city – and then trashed the place.

In doing so, it created something unique. Video games have revisited locations before, but rarely return to the exact same geometry. By sticking so closely to the first game’s map and simply roughing up the edges, Ruffian got to explore what happens when you build a game around memory, letting the lingering recollections of your previous escapades, rather than the insistent chattering of new missions, pull you in. Pacific City became host to a game about rediscovery: an adventure guided by a basic desire to see what’s happened in your absence.

So you go to that observatory nestled into the cliffs just to see if it’s survived. There was once a golden globe here you could use to hit people for an Achievement. Now the dome of the building is caved in, the windows are broken, and there’s a Freak Breach waiting to erupt in the forecourt. You go to the docks, and find the place barricaded with corrugated metal while a liner on which you once fought a boss rusts in the dock. The rooftop of Shai-Gen’s highest skyscraper – you maybe drove an upgraded SUV up the side – now rests in the centre of the nearby arcade, while, over in Volk territory, the cog monument at Hope Plaza has been pulled from its stand and lies in the dirt.

So much changed, and yet Ruffian keeps a few precious elements intact. The clumsy brilliance of the traversal hasn’t been unnecessarily refined, then, while surface detail is still ruthlessly sacrificed in order to power the fearsome draw distance. And at the centre of the city, Agency Tower still awaits those in search of the ultimate challenge. New fiction may have turned it into a glorified gun, but it remains a marvel to scramble up. Forget missions: getting to the top of the tower is still the true Pacific City endgame, and that final leap from the roof is the only true way of showing your dominance over the ruined landscape.

Sign up to the 12DOVE Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

It’s a fascinating journey, and one that has seen this playground became a rather melancholic place, despite the cheery screams of the freaks exploding under your tyres, and the Quacker mines that send bracing shockwaves through the skyscraper canyons. Perhaps the new atmosphere makes sense. After all, the Pacific City of Crackdown 2 is the perfect place to explore the dark ravages of time. It’s a landscape that’s been squeezed by the clock, subject to the passing of an in-game decade, and left shattered by a thankless real-world development schedule.

You don’t expect places in games to change. Games move on, and a series may build new cities, but the earlier ones are still there, intact, trapped on their old discs. Crackdown doesn’t play by those rules, just like it doesn’t play by the rules of cutscenes, narrative progression or empathetic characters. Whispers of your own half-forgotten hilarities lend the place shape, and playful ghosts direct the carnage.

Read more from Edge here. Or take advantage of our subscription offers for print and digital editions.

Edge magazine was launched in 1993 with a mission to dig deep into the inner workings of the international videogame industry, quickly building a reputation for next-level analysis, features, interviews and reviews that holds fast nearly 30 years on.