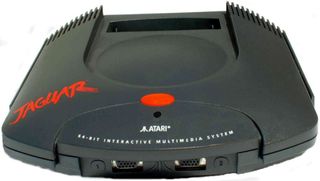

Atari Jaguar (1993)

Atari's final console fail was also its most devastating. The Jaguar was touted as a 64-bit dream machine with graphical superiority, heavy developer support and a deep library of games. When it launched in late 1993 for the affordable price of $250, these claims mostly turned out to be lies. For one, the "64-bit" promise was a bit misleading--while the console definitely surpassed the looks of its rivals at times, parts of its internal architecture were actually 32-bit. Some of the Jaguar's games turned out to look no better than Genesis or SNES titles.

And while the Jaguar was home to a few bona fide classics like Tempest 2000 and Aliens vs. Predator, its outside developer support was almost nonexistent. It was complex and difficult to program for, while its weak initial sales scared off the few studios that were interested in the first place. Many Jaguar games were ports, and only around 20 of the system's 55 total games came from third-party studios. This, combined with its horrid brick of a controller, caused the Jaguar to bomb. Just a few hundred thousand units were sold, and Atari stopped producing the console after it went bankrupt in 1995.

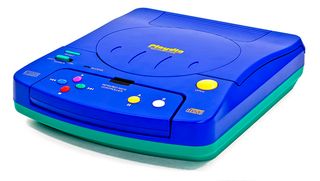

Bandai Playdia (1994)

While most of Sega and Nintendo's console competitors were releasing sophisticated, more expensive pieces of tech, Bandai decided to scale things back and release a simpler, relatively cheaper machine that was aimed towards kids. The result was the roughly $295 Playdia, which resembled a plastic blue toy, was CD-based, and was home to one of the first wireless controllers.

But when it came to the games on this games console, the Playdia was lacking. The vast majority of its titles were FMV-style interactive videos and/or edutainment software, meaning that they didn't have much in the way of actual gameplay. Bandai licensed its own popular anime series like Dragon Ball Z and Sailor Moon for certain Playdia games, but the console's limited utility kept it from ever being a hit. It was only released in Japan and--after a brief period where Bandai ironically allowed numerous hentai games onto the machine to try and salvage sales (yes, this happened)--Bandai ceased production of the console after a couple of years.

NEC PC-FX (1994)

After the TurboGrafx-16's struggles outside of Japan, NEC kept its follow-up within its native country's borders. The PC-FX was somewhat rushed into existence due to the increased compeititon, and it ultimately suffered enough losses to force NEC out of the console business for good. It was a 32-bit and CD-based, but it was shaped like a small PC tower and was made to be expandable and compatible with certain PCs.

It also had notably underpowered graphics. Instead of focusing on 3D games, the PC-FX had advanced image-decoding tech, which let it have the sharpest FMV games on the market. Impressive, sure, but by this point the market was ready to step beyond this and the PC-FX's other 2D-style titles. Developers largely ignored the outdated machine, and since the PC-FX wasn't backwards compatible with the popular TurboGrafx-16's library, it had very few quality games. When NEC realized the extent of its failure, it loosened up its software restriction policies, and a wave of "adult dating sims" soon made their way onto the console. That may have been nice for a handful of Japanese dudes, but it wasn't enough to keep the PC-FX from failing. It was discontinued in early 1998.

Sega Saturn (1994)

The Saturn sold millions of units in its lifetime, was big in Japan, and had some awesome games. All good. But in North America, and especially when compared to the Nintendo 64 and PlayStation, Sega's follow-up to the Genesis couldn't hold up. The company had already failed with Genesis add-ons like the Sega CD and, especially, the Sega 32X, but the Saturn marked the beginning of the end for Sega's days as a console making giant.

Sign up to the 12DOVE Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

The Saturn suffered from a few fatal, self-imposed flaws. For one, it was complicated under the hood, leading some third-party developers to opt for the more accommodating PlayStation. Sega's marketing strategy was similarly problematic--it was so eager to get the jump on Sony that it surprisingly pushed the Saturn's US launch date up from September 1995 to directly after E3 that year. That made it so only six games were available from at launch, which was especially weak since the Saturn was $100 more expensive than Sony's console. This botched launch helped lead Sega to lose millions on the console in its lifetime. It would stay well behind Sony and Nintendo for its entire generation.

Casio Loopy (1995)

This one was just kind of offensive. After failing with the PV-1000 12 years earlier, Casio returned to the console market with this 32-bit, light purple console, which was marketed entirely towards women. Yeah, it's that kind of thing.

Its miniscule software lineup mostly comprised of dating sims and "dress-up" games, and the Loopy itself came with a built-in printer that could turn whatever was onscreen into stickers. Somehow, this was real life. In a victory for all of humanity, the Loopy faded into the ether shortly after it launched. Only 10 games were ever made for the system.

Nintendo Virtual Boy (1995)

You all should recognize this one. The Virtual Boy's sort-of-but-not-really-virtual-reality setup was mighty ambitious, but it wasn't all that fun to use. It came at a time when the public was eager for improved home consoles, and was infamously rushed through its multimillion-dollar development process so the gaming giant could finish up its Nintendo 64 as a result.

The Virtual Boy had almost too many problems to count. It was awkwardly designed, not portable, and had just about no multiplayer features. It didn't really provide 3D games; instead, it used a 'parallax' illusion that merely showed some 3D-looking objects on a 2D plane. Its monochrome display was strictly made up of red LEDs, which kept costs down but made using the 32-bit console an ugly, migraine-inducing experience. It only had 22 games, with just 14 making it to North America. Some of those weren't any good. Its $180 asking price was too much. It wasn't marketed well either. The Virtual Boy was definitely onto something--just look how geeked people are for the Oculus Rift--but playing it was just unpleasant. Nintendo discontinued the project within a year of its launch, selling less than a million units overall.

Sega Nomad (1995)

Despite the Virtual Boy's problems, Nintendo and the Game Boy were still murdering everything else on the handheld market (including a handful of obscure devices that we didn't get into here). Sega had achieved some success with the Game Gear in the early 90s, but by late 1995 it gave the portable another shot with the Nomad. It didn't really work.

In short, the Nomad was to the Genesis what the TurboExpress was to the TurboGrafx-16. It was a portable version of Sega's popular 16-bit home console, with a colorful, 3.25-inch, LCD display and support for the Genesis's extensive library of games. It could even be hooked up to a TV and used as a more portable home console. But you know the drill with these things. The Nomad was too expensive ($180 at launch), and it ate up batteries like nobody's business. Beyond that, the Nomad launched too late into 16-bit gaming's lifespan, and it wasn't compatible with various Genesis add-ons. Sega struggled to come anywhere close to the Game Boy, again, and dropped the Nomad after a couple of years.

Apple Bandai Pippin (1995)

Tech enthusiasts may crave a dedicated Apple gaming machine today, but it's easy to forget that the Cupertino clan briefly embarked into consoles before. Like some of the computer hybrids before it, the Pippin was essentially a Macintosh in console form. It was marketed as a cheaper computer for the living room, one that could put the internet on your TV while also supporting a library of dedicated games. As with the 3DO, Apple planned to license its Pippin platform out to multiple manufacturers, but Bandai was the only one to bite.

After first arriving in Japan a year earlier, Bandai's Pippin launched Stateside in 1996 for the too high price of $600. Sega, Sony and Nintendo already owned gamers' wallets at this point, and PCs were only getting cheaper, so that cost wasn't going to cut. And despite its Mac architecture, the Pippin was remarkably underpowered for a mid-90s machine. Just 18 games were released for the Pippin and--besides Bungie's Marathon shooters--most were predictably terrible. So, to recap: high price + no games + weak processor + confused purpose = market failure. Apple and Bandai discontinued the machine the next year after selling fewer than 100,000 units.

Tiger Game.com (1997)

In 1995, American toy maker Tiger Electronics failed at broaching the handheld market with its R-Zone console, which was kind of like a poor man's Virtual Boy (that means it was really bad). Before that, it made a truckload of Game & Watch-style, single licensed game portables. Yawn. But its horribly-named Game.com--pronounced "game com--actually had an understandable premise. The idea was to be a hybrid between a game console and an internet-connected PDA. It was the first handheld to have a touchscreen, and it only cost $70 at launch.

But it failed all the same. Its display was blurry and completely gray scale. Its touchscreen was imprecise. Those who wanted to check their email, browse the web or input data had to struggle through its limited and unwieldy interfaces. Plus, this is 1997 internet, so actually using all of these features required a $50 modem add-on and a painful setup process. And yes, all 20 of the Game.com's games were ugly and horrible. Tiger launched a redesigned console to try and fix things, but this was always going to be a hard sell. Its internet focus was smart, but the Game.com sold horribly, and was discontinued by 2000.

Sega Dreamcast (1998)

The Dreamcast is the rare console that failed without doing anything wrong. It was mightily powerful, with some absolute gems in its library and an online network that foreshadowed the services we have today. It only cost $200, and it succeeded in almost every area where the Sega Saturn failed. It sold millions of units across the world at launch. For about a year and a half, the Dreamcast was realizing the future of gaming.

Then the PlayStation 2 happened, and it wasn't long before Sony's backwards compatible, DVD-playing juggernaut killed off any momentum Sega could muster. The PS2 was anticipated beyond belief at the time, so both consumers and developers fled to its already-established brand as soon as they could. All of Sega's problems then caught up to it. It was already selling the Dreamcast at a considerable loss, but its piracy issues and the 32X and Saturn's past failures only compounded its troubles. Sega just couldn't keep going financially by early 2001--especially with the Xbox and GameCube coming --and it soon announced that it would cease production of the Dreamcast to stay afloat. It hasn't returned to the hardware business since.

Most Popular