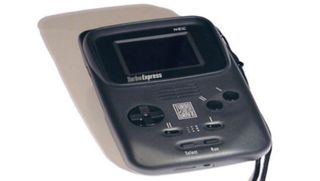

TurboExpress (1990)

We went over NEC's regional struggles with the TurboGrafx home consoles just a minute ago, but one of its more universal failures was the TurboExpress, which was a TurboGrafx-16 in handheld form. Seriously, although it looked like a black Game Boy, it played actual TurboGrafx-16 HuCards in all their colorful glory, and even could be used as handheld TV with a tuner accessory.

As you can imagine, all of this functionality came at a high price. The TurboExpress fluctuated between $250 and $300 at launch, but either way was too costly next to the Game Boy, Game Gear, or even the Lynx. Compounding this was the portable's terrible battery life, which reportedly lasted around three hours on six AAA batteries. Yikes. The TurboExpress was a futuristic, often luxurious experience for those who could afford it, but not many could, and it died without achieving much success.

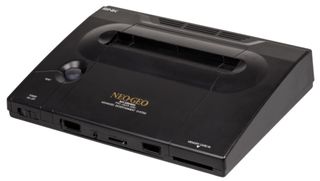

SNK Neo Geo AES (1990)

This is another instance of failure being relative. Popular Japanese publisher SNK gave consoles a whirl in the early 90s with its Neo Geo Advanced Entertainment System (AES), which effectively brought SNK's arcade games to the living room. It was a technical powerhouse capable of producing titles that looked and sounded almost exactly like their coin-op counterparts. It packed an excellent arcade-style controller, and it eventually became the first machine to use a removable memory card too. It was undoubtedly a premier gaming experience.

The problem was that it was also priced like one. SNK marketed the Neo Geo as a hardcore gamer's paradise, but unfortunately only the most hardcore would ever shell out the $650 necessary to get their hands on this bad boy. Not only that, but individual games would cost as high as $200 on their own. The Neo Geo was a beloved machine, but its asking price was just too high for it to not be a niche product. SNK released a cheaper follow-up in 1994 called the Neo Geo CD, but that console was plagued by horrendous loading times and didn't take off either. By the late 90s, the handheld Neo Geo Pocket consoles would struggle too.

Commodore 64 Games System (1990)

Commodore became a household name for gamers in the 80s thanks to its cheap yet excellent Commodore 64 personal computer. But by 1990, gaming PCs like the C64 were starting to lose their luster thanks to their renewed strength of the home console market. In an attempt to get its piece of the growing console pie, Commodore decided to effectively transplant its C64 computer hardware into a cartridge-based console package. That console was called the Commodore 64 Games System, and it was never released outside of Europe.

Dunderheaded conceptual decisions doomed the C64GS from the get-go. The C64 was already a piece of dated 8-bit technology, so the C64GS was well behind the power of the Super Nintendo and Sega Mega Drive. Many developers wanted to move on. The original C64 was also pretty cheap at the time, meaning that players who wanted the C64GS' full library of games only needed to shell out a tiny bit extra to get the fuller computer experience. The console wasn't a bad idea altogether so much as it was a poorly timed one. It didn't have many games to its name, and it went away a couple of years after it launched.

Amstrad GX4000 (1990)

The GX4000 was more or less Amstrad's version of the Commodore 64 Games System. Amstrad saw success in the 80s with its CPC 8-bit home computers, but it wanted to get in on the growing console market befwoore it was too late. So it made its own 8-bit machine that was based on CPC Plus architecture, and launched it in Europe for the low price of 99.

Sign up to the 12DOVE Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

But much like the C64GS, the GX4000 was mostly met by consumer and developer apathy. What few games it had weren't very good, what little marketing it had wasn't very worthwhile, and what little momentum it could muster was quickly crushed by Nintendo and Sega's consoles. Amstrad ceased production of the console after just a few months, and eventually left the video games market altogether a short time later.

Commodore CDTV (1991)

Fresh off of its failure with the Commodore 64 Games System, Commodore returned with another bomb in the form of the Commodore Dynamic Total Vision, or CDTV. It was essentially an Amiga 500 home computer packaged within a games console/entertainment center hybrid, which altogether looked like an old VCR. This attempt at making an all-in-one CD-ROM multimedia device became something of a tech industry trend during the early 90s.

The CDTV offered much more than just Amiga games, but it also cost $1000, which was too high for most curious consumers. Commodore was one of the first companies to get this kind of machine out the door, but that only meant it was one of the first to realize that people generally had no interest in ever buying one. Commodore would smooth things over with the Amiga CD32 in 1993, which was one of the first 32-bit systems ever produced and sold well in Europe. But a crippling patent dispute, combined with widespread anticipation for newer consoles, prevented Commodore from a worldwide launch and left it sitting on a stockpile of unsold units. The once giant company was sent into bankruptcy just seven months removed from the CD32's launch.

Philips CD-i (1991)

Philips and co-developer Sony positioned the CD-i (Compact Disc Interactive) as more of an entertainment hybrid device than a game console. It created a new CD standard for the machine and promised to give music, movies, videos and other multimedia alongside a suite of video games. It was a relatively new idea for the industry, and it was ultimately futuristic in relying solely on discs.

But man, it was just weird. That hybrid vision led Philips to not really know what to do with the thing, and the result was a wave of horrible "edutainment" content. Thanks to a busted deal where it wouldve made a CD add-on for the SNES, Philips had the rights to select Nintendo characters, and used them to make a handful of CD-i titles. If you've ever played Zelda: The Wand of Gamelon, Hotel Mario, or any other CD-I game we have in our list of the worst games ever made, we're sorry. The controller was brutal, and the whole thing cost $700. Philips deserves some praise for trying something different, but the CD-i was nothing short of a disaster in the end.

Tandy Memorex VIS (1992)

The Tandy Memorex Visual Information System was another one of those doomed interactive multimedia devices that also happened to play a handful of video games. Like the CD-i and CDTV, it looked like a big VCR and promised to give a computer's entertainment suite in a living room package. It was sold exclusively by retailer Radio Shack, and retailed for a typically obscene price of $700.

There was virtually nothing of value for gamers here, as most of the VIS' titles were of the edutainment variety. We're guessing that most of you didn't know this thing even existed, so you can imagine how well it sold when it originally hit the market.

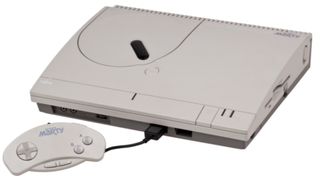

Fujitsu FM Towns Marty (1993)

Trivia time! Do you know what the first 32-bit video game console was called? (Hint: Look up.) Yep, Japan was the exclusive home to the weirdly-named FM Towns Marty, which was based off of Fujitsu's then-popular FM Towns series of home computers. It could play many games that were made for those PCs, had a built-in CD-ROM drive, and even supported some games that could be played with a keyboard and mouse. It also ended up becoming the home to a wide selection of hentai games. Okay then.

Its porn problems (or solutions) aside, the FM Towns Marty was too expensive (around the equivalent of $700), didn't have a lot of dedicated titles, and didn't generate much enthusiasm from its home market. It was a niche thing. The PlayStation and Sega Saturn were coming, and Fujitsu responded by giving up on the Towns Marty--and its short-lived redesign--within two years of its launch.

Pioneer LaserActive (1993)

The LaserActive was yet another weird, impractical, absurdly expensive all-in-on media machine that failed in the early 90s. Like its predecessors, it could play interactive music, karaoke, and videos alongside video games. It even supported 3D goggles. Like the ill-fated RDI Halcyon, the LaserActive primarily ran on Laserdiscs, or "LD-ROMs," which offered high-quality images but never caught on in North America. And again like the Halcyon, this multi-purpose device was comically costly with a launch price of $970.

That wasn't even the worst part, though. The LaserActive was an innovative, versatile device, and it was actually able to play Sega Genesis, Sega CD, TurboGrafx-16, and TurboGrafx-CD games through expansion modules. Since good, dedicated LaserActive games were scarce, this would've been appealing. But in order to play those other consoles' titles, you'd need to shell out another $400 to $600 for each add-on. At that point you could've just bought each of those consoles separately and still had money to spare. Pioneer didn't do a very good job of marketing the LaserActive, but then again we wouldn't know how to sell something this pricey either. Only a few thousand LaserActives were reportedly sold, and the machine was discontinued a year after launch.

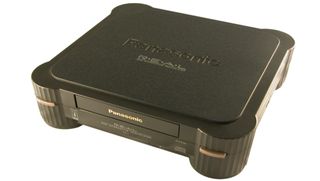

Panasonic 3DO (1993)

The most infamous of the early multimedia machine failures was the 3DO Interactive Multiplayer, a CD-based box that was also the first 32-bit console ever released in the US. It gained notable attention thanks to its technical prowess and more open business model, which was similar to what Valve is currently proposing with the Steam Box. Instead of one dedicated manufacturer, developer The 3DO Company licensed multiple OEMs to build and design their own models. Ultimately, Panasonic's rendition gained the most notoriety when it launched in late 1993.

Unlike similar competitors, the 3DO actually had some worthwhile games and developer support. Star Control II, Alone in the Dark, Super Street Fighter II Turbo, and other goodies were beloved, but they were mostly ports of existing PC or arcade games. 3DO exclusives weren't nearly as plentiful or, y'know, good. But worst of all, the 3DO's $700 launch price was just obnoxiously expensive. It never really had a chance because of it. The 3DO had money and many good ideas that would soon become industry standards, but it was gone two years after it launched. Only two million units were sold. A planned successor, the Panasonic M2, never materialized.

Most Popular