Why Netflix's Blonde fails Marilyn Monroe

It's not a biopic, and it's not her story

All biopics take creative artistic liberty – when they stretch the truth as far as it can go. But make no mistake, Andrew Dominik's Blonde is not a biopic; it's a fictionalized account of Marilyn Monroe's life, based on Blonde, a fictional novel by Joyce Carol Oates. And in this case, "creative artistic liberty" means a big-budget black-and-white exploitation film featuring scene after scene of abuse, violence, sadness, and desperation that add up to nothing. Blonde wants you to see Marilyn, the singer, the actress, the pin-up, the icon, the human being, as a victim. It wants you to think that this was her life, that this is every woman's life. "Do you feel bad yet?" Blonde asks. "Well, you should."

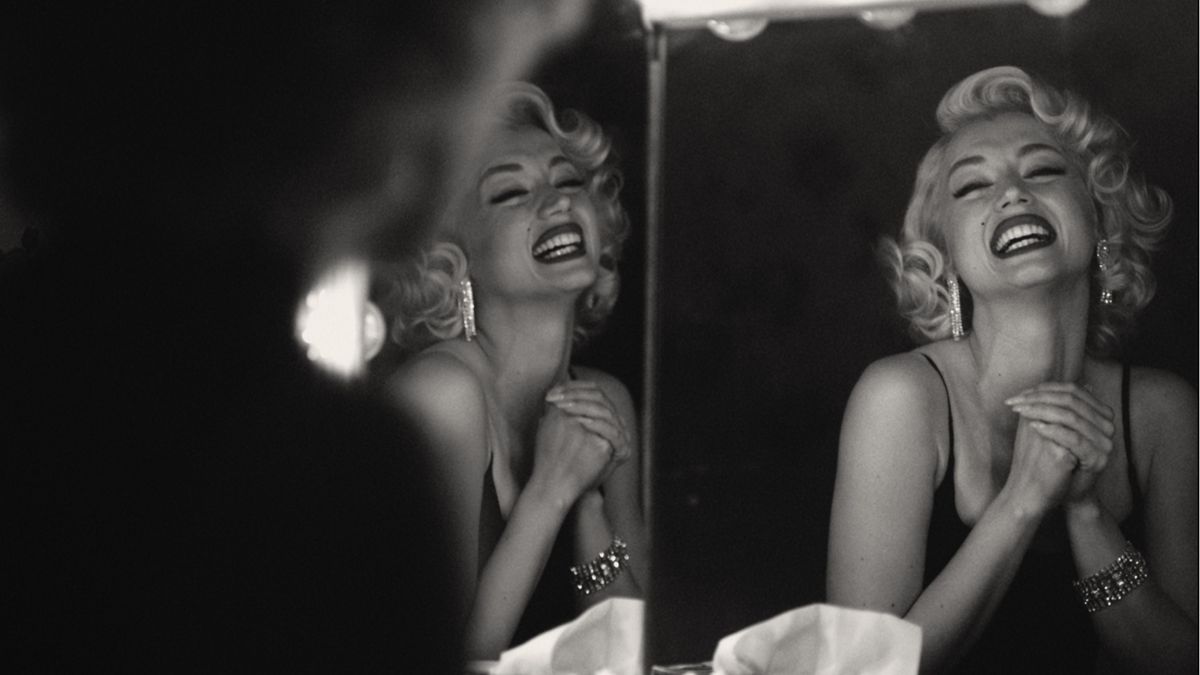

Ana de Armas stars as a version of Marilyn that we haven't seen before on screen, one that deviates from the confident and charming coquette Michelle Williams portrayed in My Week with Marilyn, or the sexy, elusive mystery that was Kelli Garner in The Secret Life of Marilyn Monroe. This is no fault of de Armas. Dominik's Marilyn is only happy in front of a camera and when she's being told what to do. The minute the camera clicks off, she immediately falls to pieces. She's joyless, confused, scared, and lost, a wide-eyed child that calls her lovers "Daddy" and is incapable of making any of her own choices (and doesn't know how to eat an egg or wear anything other than a cocktail dress). Her every move is decided for her, right down to the sexual assaults and abortions she endures throughout the film.

And these scenes are not implied or presented in a way that allows Marilyn to retain her dignity. No, the rape scene is explicit, not unlike that of Gaspar Noe's Irreversible or Michael Goi's Megan is Missing. The fictionalized moment with JFK is long, graphic, and juxtaposed with a televised rocket launch that crudely represents his orgasm. The abortion scene is filmed from the point of view of de Armas's vagina. Dominik beats us over the head with Marilyn's lack of body autonomy. He wants us to know that she is our commodity, that we own her, and that's why we "get" to see every inch of her. Dominik's Marilyn belongs to everyone but herself.

The film is a cautionary tale designed to spotlight how women are generally treated in the industry and what the women of yesterday went through in the days of Old Hollywood – but it's not Marilyn's story; it uses Marilyn to get the point across. It's been documented that many Old Hollywood actresses were forced to get abortions because their contracts presented them with the ultimatum of either having a child or losing their entire careers. Why use Marilyn to tell the story of other women instead of just telling Marilyn's story?

It's been written in countless books and biographies that Marilyn suffered from miscarriages and that she wanted kids. (In all fairness, this is what the book does, but the movie is being presented by Netflix as a biopic, not an adaptation. It's not even in the end credits of the film.) Instead, Blonde's Marilyn sees an aborted CGI fetus crawl out from her vagina and speak, directly asking her why she "killed" it in the first place. It was this scene in particular that had me wondering, who is this for? Who needs to see trauma presented like this?

In the end, Blonde is the type of movie that men will come away from believing that they are smarter and more in tune with what women go through after watching. The woman is weak, the woman is failed, the woman can't rely on anyone around her, so what else is she to do but die? And that's the thing: the film builds and builds and builds on Marilyn's torment, but there is no silver lining or happy ending. It's a rape-revenge movie without the revenge.

We all knew that Marilyn would die. Overcome by sadness, Marilyn takes her own life. Roll credits. In the book, Marilyn is killed by the government for knowing too much about JFK. If this were kept in the film, the unnecessary JFK rape scene would have at least made sense. It's not unlike Promising Young Woman, a rape-revenge film that had many men leaving the theater feeling like they finally understood the plight of the woman (though I truly believe the film intended to send a message of empowerment, despite its bleak ending). At the end of the film, Carrie Mulligan's character - who spends the entire movie tricking, trapping, and getting revenge against the world's scummiest men – is killed by a man. A man comes away from the film thinking, wow, there really is no happy ending for the woman who endures so much. Blonde is the same way: 'all we do is suffer.'

Sign up for the Total Film Newsletter

Bringing all the latest movie news, features, and reviews to your inbox

But we don't. There's a fascination with women and trauma. Marilyn was smart as a whip, put in long hours and hard work, and enjoyed learning her lines and being in the spotlight. She was bright and dazzling. The film is not concerned with any of this: it doesn't see the point in depicting the woman as a human being, as a pillar of strength, a beacon of light, or celebrating the way she perseveres in the face of oppression. We are all of these things and more.

Andrew Dominik's Marilyn is a child in high heels, playing dress-up at all times without any confidence underneath her red lipstick. She's an allegory, a sad warning story about what men think it means to be a woman. Blonde is not a biopic, it's an artsy exploitation film that uses a dead woman's legacy to make a point.

Lauren Milici is a Senior Entertainment Writer for 12DOVE currently based in the Midwest. She previously reported on breaking news for The Independent's Indy100 and created TV and film listicles for Ranker. Her work has been published in Fandom, Nerdist, Paste Magazine, Vulture, PopSugar, Fangoria, and more.

Most Popular