Why you can trust 12DOVE

Floating assistance by Jio Butler

Sheet music by Ewan Barry

Moral & technical support by Paul Duffield

Panty advice by Hayden Scott-Baron

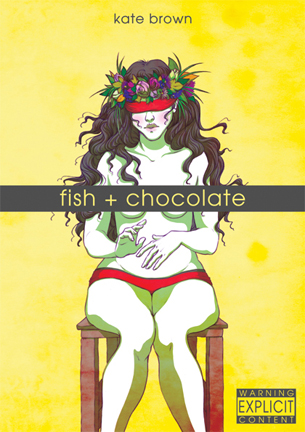

Fish & Chocolate is a collection of three short stories that explore the relationship between mother and child. I don’t know what genre they are. I know that doesn’t matter. In the space of 140 pages, Kate Brown’s precise, intricate scripting and incredible grasp of character leads you through horror, fantasy, “literary fiction” and a good chunk of what’s in between.

“The Piper Man” opens the book and follows Marie Nicholas and her sons, Ben and Matthew. Marie is a journalist, always working, always talking and always home. She loves her children, she loves her career and she loves the sense of freedom that working from home brings her. The relationship between Marie and her boys is elegantly sketched out, and we know just how bad the divorce was from an especially affecting kind lie from Marie at one point. Brown’s keen eye for detail doesn’t blink for a second, and the scene in which Matthew asks for a TV in his room is a universal moment that carries huge emotional weight. She’s not thriving, but she’s doing well and, for all the problems, so is her family.

Brown cleverly uses the angle of panels and the page design as a whole to add an extra dimension to these scenes. One in particular sees Marie start off a phone call full of confidence and finish it deflated and not quite defeated. It’s a smart idea and Brown plays with this over and over again. “The Piper Man” of the title is another good example, almost always sitting down or crouching, never quite at the same level as the adults in the story. He’s always focused on the children and always talking eye to eye. He’s also deeply, viscerally unsettling, especially in his final appearance. There’s a constant, escalating tension throughout the story which explodes in the final pages in a way I’ve never seen done this well before. Space and scale are used to create a sense of menace, then horror, then the absolutely impossible and Brown keeps the focus on Marie the whole time. We know exactly what’s happened, we know exactly the price Marie has paid and we know this without a word being written on the final pages. It’s chilling and will haunt you almost as long as it will haunt Marie.

“The Cherry Tree” takes the space explored in the final pages of “The Piper Man” and turns it into a blank canvas. A young musician and her daughter move to a sprawling house with a magnificent cherry tree in the back garden. What’s not said, but implied, is they’ve moved here so the mother can write. In practice, she struggles to fill the huge spaces of the house, drawing further and further into her process as her daughter, Prisca, literally blossoms. The cherry tree is a defining point in her life and again, Brown uses the geography of childhood and the emotional milestones we all pass to create a story that’s as touching as it is universal. Prisca’s triumphs and horrors will be familiar to lots of readers, and the creative struggles of her mother will be familiar to many more. When the two combine, the effect is horror of a very different sort to “The Piper Man” as Prisca discovers just how much her mother is struggling. The ending echoes that of “The Piper Man”, but does so in a way which is noticeably more helpful, if somehow just as dark.

Special mention has to be made of the stunning page layout in this story too. One page shows the mother, working at the piano inside the house, which is in turn set in a full splash page of the garden outside, whilst another shows how Prisca’s universe is defined by the cherry tree. It’s difficult to talk about written down but suffice to say that these scripts are so nuanced and well-designed that even the page layout is used to further the story. This is as high end as graphic storytelling gets but it never feels inaccessible, cold, or falsely worthy.

Likewise, “Matryoshka” , the last story. Named after the Russian nesting dolls, it’s a story about the raw grief of losing a child and, again, the empty, numb spaces that your life is filled with afterwards. There’s a beautiful design choice here once again, as the lead sits still and a friend bustles around her, her speech bubbles only partially visible. Grief, and trauma, of a certain level, does that exact thing; turns the volume down on the world and it’s yet another example of the book’s design being used to forward the story. That’s also reflected in the script for this final piece, as the lead here – a woman who’s already lost so much – finds something: peace. The imagery of the final pages is again huge and open and deeply personal, as she makes peace with her loss and begins the long process of restarting her life.

Fish & Chocolate is stunning. Again and again, Brown plays with format, genre, size and volume to create stories which are horrific, fantastical and incredibly intimate. This is a truly beautiful book, involving and clever and personal and filled with that summer chill that only the best British supernatural fiction. A major talent is at work here. Do yourself a favour, and pay attention.

Alasdair Stuart