Black Panther and the revitalization of T'Challa with Christopher Priest

An oral history of Christopher Priest's Black Panther, from Christopher Priest himself

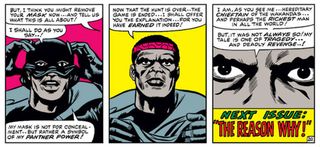

Marvel's Black Panther has been around since the '60s, and has had many different incarnations – the intense, involved storylines of the '70s by Don McGregor and Billy Graham, the over-the-top adventures by Jack Kirby, the high-profile run by Reginald Hudlin and John Romita Jr, and the recent by Ta-Nehisi Coates, Brian Stelfreeze, Daniel Acuna, and others.

But there was never quite a version like Christopher Priest's.

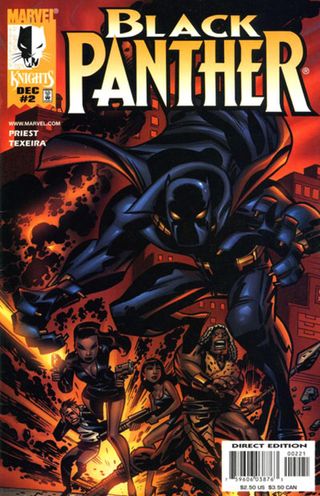

As part of the Marvel Knights line that helped revitalize Marvel in the late '90s, Priest's Black Panther was a book that was equal parts urban vigilante, political thriller, and a satire where the devil gave a guy a pair of pants he couldn't quite get rid of.

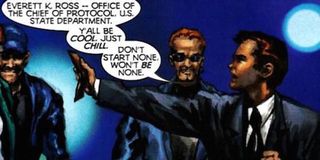

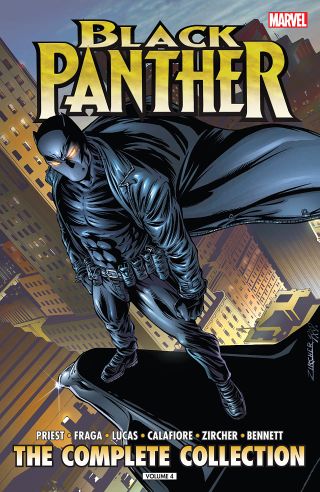

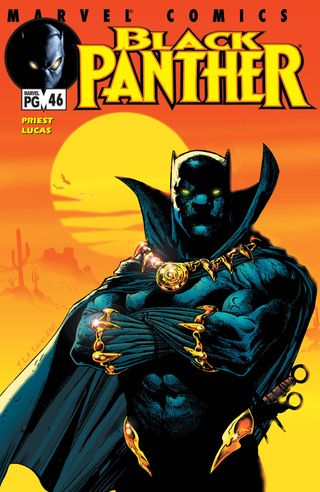

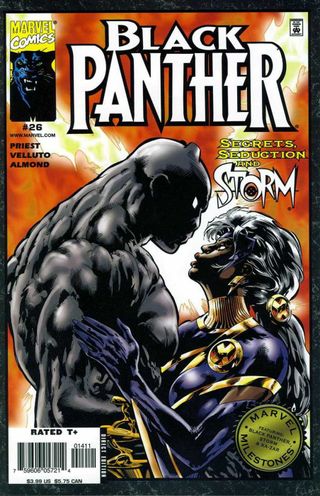

Over the course of 62 issues – the last of which saw the character literally dropped as the hero of his own book – Priest and artists, including Mark Texeira and Sal Velluto, crafted the dense tale of T'Challa, King of Wakanda, whose skills as a fighter and leader were well-matched by his craftiness and manipulations. Initially exiled to America (and overseen by "Emperor of Useless White Boys" State Department rep Everett K. Ross), the Panther's tale soon expanded to encompass the elaborate power structure in Wakanda, the tribal traditions that kept his followers near, and his own demons – and cemented the Panther as one of the most cunning, manipulative minds in the Marvel Universe.

Back in 2015 coinciding with the publication of Black Panther by Christopher Priest: The Complete Collection, Newsarama talked at length with the writer to take an extended look back at his run in a three-part conversation. Over the course of our conversation, we got some candid insights into what it was like creating the book, and his thoughts on the character of T'Challa – past, present, and future.

Newsarama: Priest – first off, how's it feel to see these stories collected and reprinted?

Christopher Priest: Actually, I don't know; I haven't seen the volume yet. But I've just been notified of a FedEx delivery so I'm assuming the volume is in it. That or, you know, a pipe bomb.

Comic deals, prizes and latest news

Get the best comic news, insights, opinions, analysis and more!

I'm happy Marvel chose to collect the series. I'd been told previously that a collected edition would never happen because the character and series had been retconned by Reginald Hudlin, and that was now the official version of Panther Marvel was promoting.

This also marks the first time my name has been part of a Marvel title, which would make my mom happy if she were still with us.

Nrama: What do you remember the most about that time in your life when you were doing Black Panther?

Priest: The constant uphill slog to woo fans of mainstream Marvel comics. Post-Marvel Knights, there was constant and unrelenting pressure to get our numbers up. It was not healthy for the creative process.

I never had editorial or creative control over the book; all of the shifts in approach and changes in the narrative were suggested by Marvel, including replacing T'Challa with Vin Diesel toward the end in a desperate flailing to keep the book alive.

Marvel executive editor Tom Brevoort was likely the only guy to admit, at least to me, that Black Panther is whatever it is, and whatever it is is very closely tied to its writer (meaning me). Some people will like it, some won't, but turning ourselves inside-out chasing numbers was a bad idea.

Successive writer Reginald Hudlin recognized this immediately, and, as he described to me, didn't even bother trying to pander or worry himself about numbers.

I didn't want to write a 'black' book because Black characters are a tough sell. I go into my reasons why in some detail here.

Nrama: How did the book come about?

Priest: Joe Quesada and Jimmy Palmiotti inked a deal with Marvel to launch their own imprint, called Marvel Knights. I'd heard they were taking over Daredevil, and was very excited when the phone rang. I love Daredevil and had always wanted a shot at (the character). When they said "Black Panther," my heart kind of sank.

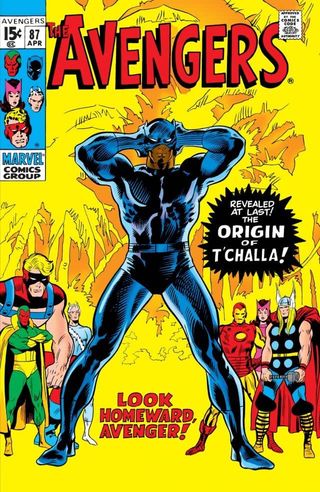

See, in those days, writers were expected to more or less maintain the status quo. The status quo for Panther was this colorless cypher who sort of stood in the back row for the Avengers class picture.

Joe and Jimmy, along with editor Nanci Dakesian (AKA Mrs. Joe Quesada), DC editor Brian Augustyn and Mark Waid all kind of talked up the project, but I was concerned about being typecast as a 'black' writer, and really wasn't thrilled about the character, even with the unique 'Coming To America' spin the group had put on it.

So I gave Joe the Robert DeNiro speech from Casino: "Okay, Joe, but if I do it, I have to do this my way. I mean it, no interference."

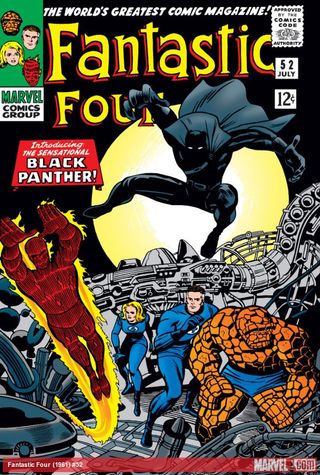

Basically, I couldn't write this dull guy who routinely got clocked over the head and dragged behind pickup trucks. I had to write the guy Stan Lee wrote way, way back in Fantastic Four #52: a guy who out-foxed and beat four of Marvel's most powerful heroes.

If I could make Panther tough, mysterious, wily, and often at odds with his Avengers comrades, that was a character I'd find interesting. If he could embrace his monarchship the way Namor does - perhaps not as arrogant, but surely as confidently, a man of supreme power and dominion--that would interest me as well.

Lastly, I told them we needed a point-of-view character: someone who could validate the fears and presumptions of white superhero fans who'd surely be reluctant to buy a 'black' book.

I had sometime before created this character, an attaché (i.e. diplomatic flunky/babysitter) over Ka-Zar and had modeled him roughly after Michael J. Fox and Matthew Perry. I thought somebody like that might make a great point of view character for Panther.

Marvel Knights agreed, and I signed on for the series. I turned in the first issue, and Jimmy and Joe rejected it. We were off to a great start.

They explained to me that they loved the 'Pulp Fiction In Rewind' narrative approach I was using in Quantum & Woody and thought it would work really well for Black Panther. So they booted #1, which had originally been written much more traditionally, and we imposed that narrative style which was both loved and hated. Ironically, skip ahead 20 years, and the new Valiant booted issue #1 of my Q2: The Return of Quantum & Woody for much the same reason.

Nrama: So let's look at the initial storyline of the book and the situation you were in with Marvel Knights – this was, at the time considered something of a crazy experiment. It changed things at Marvel, it set the tone for the modern superhero book and movies, but at the time, Marvel's recently declared bankruptcy and the company's future is in question. What was the environment like to produce this title?

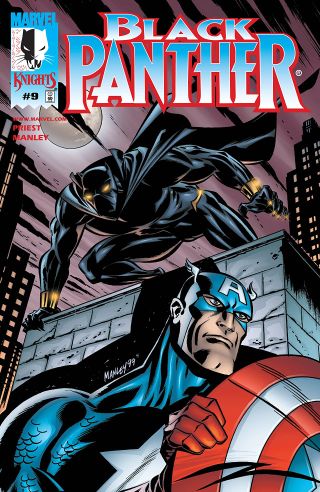

Priest: Oh, I was mostly insulated from all of that. Joe and Jimmy preferred Black Panther take place largely within its own bubble, even as I would shoehorn the Marvel Universe in, specifically with the storyline 'Enemy of The State,' where Panther admits he only joined the Avengers in order to evaluate them as a possible threat to Wakanda.

See, it made absolutely no sense to me why Panther would ever join a super-hero team; he's not a super-hero, and the record shows he did a whole lot of nothing most of the time. Why?

After Marvel Knights handed the book back to Marvel, I was tasked, from that point until the book's cancellation, with trying to grow the audience. It was exhausting and it inhibited most creative thinking.

We tried everything, every possible guest star, every gimmick we could think of. In retrospect, I believe Joe and Jimmy were right: we should have just done our thing and largely ignored the Marvel U. Pandering in an attempt to raise sales proved, ultimately, to be a waste of time.

This was, chiefly, Reginald Hudlin's thinking when he launched his version of Panther. Not speaking for Reginald, but, as he explained it, he realized we'd tried every trick in the book to broaden the appeal in an attempt to woo more readers and had failed.

So Reginald didn't see the point of doing that, and from the start simply chose to write a good book and invest himself in the work rather than constantly worry over sales figures. And you know what? His book vastly outsold mine because the investment was in doing good work and not constantly struggling to win people over.

And if I may: fan (and some staffer) speculation about there being some kind of 'feud' between Reginald and myself is just stupid. We've been friends for more than 22 years. Denys Cowan had his version of Panther, I had mine. Reginald honored me, frankly, by smartly keeping things he thought worked and jettisoning things that didn't. And his version outsold us all.

Ironically, some fans gave him grief over going his way just as fans (and some pros) gave me grief for going my own way. I'd never do that, and I wasn't even aware of this myth circulating because by the time Hudlin's Panther launched, I was way, way out of comics altogether and, frankly, not paying a lot of attention to any comics-related stuff.

I seem to recall hearing about the new Black Panther and being happy (and a little surprised that Reggie had the time to write comic books), but, frankly, my head was in Christian ministry and I believe I was pastoring a church at the time and just not paying a lot of attention to comics.

Nrama: You used a lot of the character's previous history in comics -- there's a great deal from the Don McGregor run to start, and those Kirby homages with the frogs. What Black Panther stories had the greatest impact on you before you were working on this book, and why?

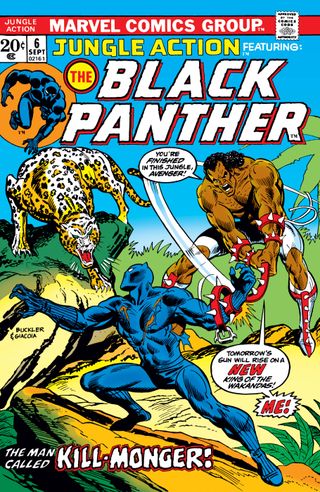

Priest: I didn't read Marvel Jungle Action when it was actively publishing. It was a stupid name for a comic series (with due respect to Archie Goodwin and Stan Lee, who were, I believe, running the joint in those days). The title was incredibly patronizing, falling just short of Jungle 'Bunny.'

I was a kid growing up on New York City streets, I had no interest in the jungle. I liked Hero for Hire, though I couldn't imagine who thought up the ridiculous speech patterns for Luke Cage. I also thought Black Panther was boring because he had no powers and (no offense intended) Marvel seemed to demonstrate the character's courage by having him get shot and stabbed and hit over the head. Kirby's Panther was even more off the grid to me.

Once I began researching Panther as a comics pro (whatever that means), I tended to agree more with McGregor's Panther than others. His obvious investment in logically thinking through the basic realities of the African continent and his fleshing-out of Wakanda are amazing and valuable assets to the Marvel Universe

His Jungle Action mega-arcs, what has been lauded as 'Marvel's first graphic novel,' were a real gift, and I saw no need to retcon, ignore, or otherwise do away with what he or subsequent writer Peter McGillis created. McGregor created an amazingly detailed Pantherverse with which I mostly agreed and was immensely grateful for all the tools he left in the toolbox.

Denys Cowan and Dwayne Turner's visions of Wakanda, as an ersatz African Epcot Center, opened my eyes to the unexploited possibilities; these men, both of whom are African American, together with writer Peter B. Gillis, created an African Asgard of sorts, and I just went, "Oh, my."

Actually, now that I think about it, Denys worked on Panther, Reginald Hudlin worked on Panther, and I worked on Panther. Marvel should create a Milestone Black Panther book. I'm quite sure, if it wouldn't blow up Milestone's deal with DC, we'd all be eager to see what could be done with the character in a creatively uncompromised environment. We all dearly love this character.

Where paths diverge between my vision of Panther and those previous is the character of T'Challa himself. I can't speak for Mr. McGregor (whom I do not know), but my impression was he saw Panther as the ultimate realization of human potential whose bravery was exemplified in his willingness to risk his life in the service of others.

I see T'Challa that way as well, but I defer to Stan Lee, whose bedrock for this character was he was a man who outsmarted Reed Richards and out-fought the Thing. Those key notes seemed missing from McGregor's Panther, and to me Stan (whom I do know) is Moses; his original concepts are the stone tablets of modern comics.

Thus, it made absolutely no sense to me that Panther wouldn't at least nominally protect himself from things like small arms fire or stabbing weapons, and that, at the very least, he'd carry an iPhone (which is what his Kimoyo card essentially is).

The fan outrage was unexpected and a little off-putting, considering how poorly supported Panther has traditionally been. It seemed to me like, 'We're not actually going to buy any Black Panther comics, but how dare you make him smarter and more technologically advanced! Bring back the plain old spandex and get rid of the gadgets!'

This seemed nonsensical and a violation of Stan's character; Marvel fandom having grown so accustomed to what I considered to be an errant interpretation of Stan's original concept. And these folks weren't buying McGregor's book or mine, so why on earth should Joe and Jimmy pay the 'outrage' any mind?

I just used Stan, and only Stan, as my template - though I wanted a more laconic, more Batman-esque, and mysterious character to Stan's friendly and gregarious monarch. I didn't think Panther would talk all that much. I thought Batman talked too much (and maybe still does, I don't actively read comics anymore); like all that yakking he does explaining his motives in the final moments of The Dark Knight; it was a violation of his character to stand there yammering. Not Batman.

I thought Panther could and likely should have been the Batman of the Marvel U. That character archetype was missing from Marvel's pantheon, and Panther's origins and motives are different enough from Batman's to prevent him from being called a Batman rip-off.

If anything, now that Batman has become Iron Batman, with all that stupid armor and tech - wrong, wrong, wrong, wrong DC - he is following T'Challa's lead and not the other way around.

The main thing preventing Black Panther from fulfilling that Batman niche for Marvel is, frankly, Marvel. Whether knowingly or subliminally, Marvel marketing - if not Marvel editorial - sees Panther in a racial context and, thus, as a less 'pure' character than, say, Drax the Destroyer or the Sub-Mariner. I don't mean racism so much as a level of sensitivity and concern for the reader's ability to identify with and/or respond to these issues.

For example: a line was cut from my contribution to the recent Deadpool marriage issue because Marvel was concerned Black readers might be offended. I assured them Black fans would not be offended by the line, but I was overruled. Which troubled me because I was an actual Black person assuring them Black people really aren't as thin-skinned as they (or the corporate hedgehog above Marvel editorial) may think.

Black people have a sense of humor. Deadpool, the character, busts on everybody. It was a violation of his character for him to start pulling his punches just because he was talking to a Black person.

Marvel and DC should stop being afraid of letters, afraid of email. The incident struck me as a little silly, that Marvel wasn't so worried about their Black fans as they were perhaps worried about offending the sensibilities of their white fans and/or of ‘Pool coming across as racist.

It wasn't a racist line. It was, however, the funniest line in the story and they cut it, despite having an actual Black person assure them. If they actually understood humor (or Black people), they could have run one of those old Stan Lee asterisk captions; *We were assured, by an actual Black person, that this line was okay - Ed.

This is what I mean by a creatively compromised environment. This wouldn't happen at, say, Milestone. They'd say either the line was funny or it wasn't, Either ‘Pool was in character or out of character, and that would be the only criteria they would use. Larry Hama, my mentor, taught me that humor involves risk. There was rarely an issue of Crazy Magazine we published without being convinced we would be fired for it. Everybody, of every ethnicity, was fair game.

In terms of character, Panther shares a great deal with Sub-Mariner - who himself is not white but appears white and therefore can navigate the Marvel zeitgeist more easily than can Panther. Panther is a king. Kings are different kinds of folk, and frankly, I hadn't seen a proper response from the US government in previous versions of Panther. He wasn't greeted like a king or, frankly, monitored as we would any head of state wandering around Brooklyn.

This was the attitude Everett K. Ross brought with him when he drove to LaGuardia in his Mazda Miata to pick up the king of a sovereign nation. For me, Ross embodied decades of, no offense, disrespect not of Panther but of Stan Lee. Stan's Panther was a mysterious monarch of a hidden kingdom but was someone so respected the FF flew all the way to Africa - with great apprehension and nervousness--to meet.

It seems, after Fantastic Four #52 and #53, everybody kind of forgot who Panther was and treated him like Joe Blow. King T'Challa is not Joe Blow.

So I vented my irritation at how Marvel had so marginalized this character (which I interpreted as Marvel editorial approaching the character from a standpoint of race) through the over-the-top stupidity of his new State Department handler: he saw Panther the way Panther had ultimately come to be seen by Marvel: Just Some Guy who was routinely overshadowed by heroes in which they were more invested. Confounding the low expectations for the character was, to me, Job One, and Ross was the tip of that sword.

If we could all take race out of our minds where it applies to Black Panther, there's no reason why Panther could not or should not be Marvel's highest-grossing franchise. He isn't because neither Marvel nor comic book fans can neutralize the role race plays in terms of connecting with an audience, most especially with a character that literally has the word 'black' in his name.

I did not, however, want to disavow anything that had gone before. I know what that feels like, to have somebody come along and suddenly nothing you did ever happened. I think part of the fun of being a comics fan is seeing how writers solve problems within the rules and within the history of the universe.

These days, the fad seems to be every writer gets to shake up the Etch-A-Sketch and pretend no other stories had ever been written about the character, and both majors seem overly eager these days to blow up their continuity every time sales dip.

I went too far in the other direction, hoping to salvage every previous appearance of Panther, including Jack Kirby's campy version, which we refer to as 'Happy Pants Panther.' Don McGregor's version wasn't entirely my cuppa, but Don did a lot of heavy lifting in terms of making Wakanda real and fleshing out Panther's supporting cast.

I saw absolutely no need to just retcon everything, though that option was presented to me. Don's supporting cast worked quite well, and the brilliant and respectful literalism with which he approached the series was certainly closer to my point of view than the generic Kitty Man who hung out with the Avengers - no offense intended to Roy Thomas or anyone else; I just thought there hadn't been enough investment made in the character.

Nrama: For that matter, what was most appealing to you about the character, and what do you feel was often misunderstood about him?

Priest: I've got to be honest: the character never appealed to me until Joe and Jimmy (and Mark and Brian) began to engage me. I was ready to pass. I was arriving at a point in my life - where I am now - where I no longer take gigs just for the rent money; it's got to be something I'd actually like to do, and something I believe in.

Nrama: You were telling me a bit about the art for the initial arc and Mark Texeira before we officially started this interview – are you okay with repeating that here?

Priest: Yeah, that's fine. Joe Quesada was the layout artist under Tex's gorgeous artwork. Joe is a simply amazing storyteller.

I've been listening to a lot of film commentaries lately and am really impressed by how nearly everyone involved with a film production is concerned about story. I mean, from the executive producers to the lowliest intern or gopher, everyone is talking about, thinking about, breathing story, character; invested in storytelling.

In comics, my experience has been mostly artists whose visual storytelling chops are either weak or they're more invested in rushing to a paycheck than in doing work they can be proud of.

Alternately, there is the ego: artists who ignore the stage direction in my scripts not because they necessarily disagree but because they want to draw lots of poster art for resale or their ego insists they make another choice because they're not about to let some writer tell them how to layout a page.

In most cases. the storytelling suffers or becomes indecipherable. The problem is, the art continues to look very nice, but the reader can't make heads or tails out of what is going on, and I end up reading about what a lousy writer I am.

The end-user usually has no way of knowing the artist failed to follow simple and clear directions and made changes for no other reason than they are either (a) egotistical or (b) lazy. But, inevitably, I am the one who gets dinged... every time.

This is a primary reason why I stopped writing comics. It is incredibly demoralizing to be raked over the coals by the editor on the script, rewriting and polishing and dealing with all the scrutiny most editors afford the script, only to have the same editors take a nap, apparently, when the art starts coming in, often not even realizing the art bears little resemblance to the script until they start having problems with the lettering balloon placement, realizing some sequences make no sense because the artist did not follow the script for whatever reason.

I remember getting attacked online for 'blaming the artist,' which I'm not actually doing. All I'm saying is, the script said, "Bobby ate an apple," and the art has him wrestling an alligator. I didn't write that. The artist wrote that because, at some point, the artist decided he knows better than I do.

This does not happen in film. Everyone I've talked to or listened to is hyper-focused on making things clear and telling a story. But, with notable exceptions, my comics kept coming back as train wrecks. It was demoralizing and I just finally said the heck with it.

The early issues of Black Panther were laid out by Joe Quesada, his layouts lying beneath the gorgeous Mark Texeira art. Now, Joe was my boss, but Joe followed the script to the punctuation mark.

The opening sequence of Black Panther #3, I believe, has the villainous Achebe chasing a man, and we see the chase through a sequence of tight shots, and then we waste two entire pages on a spread of the master aerial shot of the desert, with the two tiny figures racing across it.

Nine out of 10 artists I've worked with would have ignored that stage direction and would not have wanted to 'waste' two pages on a plateau of sand. But Joe 'got' it, and instead of indulging his ego on poster shots or changing the angle so he could get his artistic rocks off, Joe remained disciplined and trusted the script. The result was a powerful introduction to this maniac character who chased a man across a desert for selling his ex-wife a pair of shoes.

I'm not a genius and this isn't some backward ego stroke for Priest; I'm just saying that was the best example of the artists trusting the script and not fighting against it.

Best experiences includes Sal Velluto on Black Panther, who would take liberties but never for ego's sake, and the pages would always come in as good as the script or better, and Joe Bennett on The Crew and Captain America and the Falcon-- particularly the 'wedding ceremony' scene between Cap and the Scarlet Witch, which Bennett followed very faithfully but, wow, made it so much better; a scene taking place on multiple levels as Wanda shares her morning tea with Steve Rogers in a pseudo-Japanese wedding ceremony. Brilliant.

I was trained in storytelling by Jim Shooter, Stan Lee, and Larry Hama. Doesn't make me a genius, and there really isn't anything fancy about the stage direction in my scripts. I honestly don't care if an artist goes their own way; just make it as good or better, and don't just change things out of ego.

A recent project came out looking nothing at all like my script. Important storytelling elements were compromised or ignored, losing at least a third of the story because that one-third was not in captions or dialogue, but in pictures the artist chose not to draw.

I mean, it was as if the artist began each and every single page by thinking, 'Okay, I'm not sure what I'm going to do on this page, but I know I'm not going to do what the script is calling for.' He changed every angle of every panel of every page and ignored my repeated pleas to 'please, please, please follow the script or at least tell me what's bothering you and I'll rewrite it.'

And it reminded me why I stopped writing comics altogether, the often contentious relationship between collaborators. At least, when I'm writing novels, it's just me and my editor. I mean, the typesetter doesn't change my plot because he sees things differently.

Back to the film commentaries...

Every actor, every grip, every editor - talking about story, story, story: how to convey the story, how to make it clear. Hollywood is, of course, loaded with egos, but it's amazing to see how, despite the egos, those collaborators pull together and focus on telling a story rather than butt heads and sabotage what is extremely hard work and investment just because their ego apparently demands it.

Nrama: With your initial arc of Black Panther, you isolated the Panther from Wakanda. What was the main reason for this?

Priest: To get him to the states and keep him in play. Otherwise, he'd have returned to Wakanda too quickly, and I did not want the series set in an exotic Neverland; I wanted it to be set in what Stan called "the world outside our window."

Nrama: I want to talk about the development of the supporting characters. To start, let's talk about Everett K. Ross, Emperor of Useless White Boys. How did this character come about?

Also, what do you make of some reactions people had, and how some felt the Black Panther book was more 'relatable' with a white, American guy narrating it? (Yes, that's an 'Ugh' I'm making).

Priest: Actually, that was the main purpose for including Ross, who was originally a character in Ka-Zar. Comic books are all about selling fantasies. All people - white, black, whatever - are tribal in the sense that we relate to that which is familiar to us.

"Black" comic books traditionally do not sell well, another reason I was reluctant to take on Black Panther. Comics are traditionally created by white males for white males. I figured, and I believe rightly, that for Black Panther to succeed, it needed a white male at the center, and that white male had to give voice to the audience's misgivings or apprehensions or assumptions about this character and this book.

Ross needed to be un-PC to the point of being borderline racist. I am surprised, still, that Joe and Jimmy Palmiotti and Nanci Dakesian allowed some of his lines to get through, like his belief that he'd hear lots of Black people singing in the streets of Brooklyn. "I was lied to...." or that, arriving at his hotel, Panther would just "order up some ribs."

I don't think Ross was racist at all. I just think that his stream of conscious narrative is a window into things I imagine many whites say or at least think when no blacks are around; myths about Black culture and behavior.

I was also introducing a paradigm shift to the way Panther was to be portrayed; somebody had to give voice to the expectation of a dull and colorless character who always got his butt kicked or who was overshadowed by Thor and Iron Man suddenly knocking out Mephisto with one punch. I mean, he runs into the room, Ross says, "Should we call the Avengers?!" Panther says, "Why?" and just decks the guy.

To me, that's Black Panther. It's not arrogance, it's competence.

There needed to be a character in the story who would react to that; who would comment that this is not at all the Panther Marvel fans had come to expect.

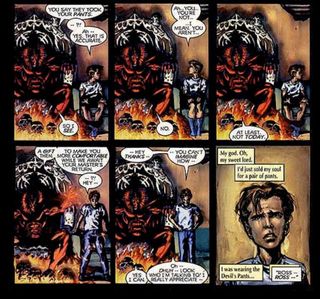

Nrama: And let's also talk about Ross' pants.

Priest: It was just a bit of business that we milked for comedy - Ross having his pants stolen by thugs and Mephisto giving him magical pants he couldn't take off. I mean, I just made that up as we went, we didn't invest a lot in it.

Nrama: And there's Zuri and the Dora Milaje.

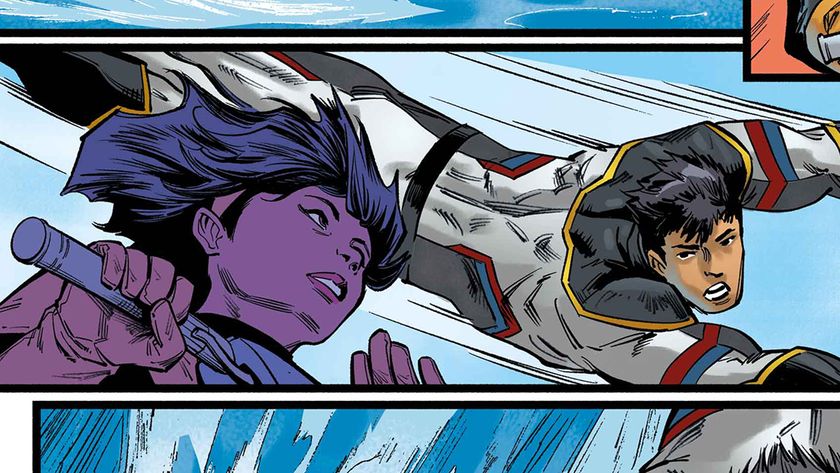

Priest: These three were my main contribution to the Panther legend. It made sense to have some wise elder accompany him - even though Zuri's presence was largely comic relief and ceremonial. The 'brides in training,' his bodyguards the Dora Milaje, grew out of Don McGregor's brilliant concepts of tribal castes within Wakanda, which made perfect sense.

How does Wakanda avoid the kind of splintering and tribal warfare that riddles the continent? He keeps a representative from the two major tribes in a kind of G-rated harem. So long as he doesn't, ahem, close the deal with either of them, Wakanda's tribal factions remain in a state of détente.

Should he choose one over the other, that could lead to tribal strife (hence the business with Man-Ape / Queen Divine Justice and the chain of events set off by Mephisto's illusion, where T'Challa ends up making out with Nakia - named for my niece - in the back of the limo, and Nakia subsequently going nuts and becoming the villainous Malice).

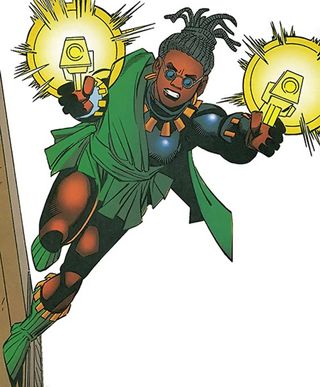

Nrama: And what about Queen Divine Justice (and her relationship with Vibraxis from Fantastic Force, aka NFL)?

Priest: [laughs] "NFL!" I can't even remember why she called him that.

Nrama: It was short for "Nappy ‘Fro Lad."

Priest: [Laughs] Ok, sometimes Marvel does need to stop me! Queen Divine Justice was, blatantly, Robin to Panther's Batman. In retrospect, I'm not sure she added much to the mix, but was part of our never-ending attempts to build Black Panther's numbers.

She was the latest iteration of my niece, Candace, with whom I fell in love when she was about 18 months old. Candace has appeared as numerous characters, most especially Natasha Irons, John Henry Irons' niece in Steel.

The real Candace was about the single most annoying teenager I'd ever known, but she could get me to do virtually anything she wanted. Now all grown up with a PhD, I'm so very proud of her, still madly in love with her, and, yes, she's still annoying.

I brought Vibraxas in as means to resurrect the villainous Klaw. I wanted to hold off using Klaw as long as Marvel would allow, mainly because whenever anybody got their hands on Panther, they immediately went to Klaw (whose origin is tied in to Panther's). From my distance from it, it appears the movie folk are doing this do - go directly to Klaw - which has its plusses and minuses.

By the time I felt safe to deal with Klaw, I wanted some interesting misdirect with which to reveal and reintroduce him, hence Vibraxas. Hooking him up with Queenie was kind of an afterthought, and Panther sort of mentors him a little in Black Panther #23, one of my favorite issues (with some amazing character work by Sal Velluto and Bob Almond).

All along I'd planned some deeper and difficult tribal connection for this kid, the subtext being we - all African Americans - have a rich heritage far too many of us know nothing about. Chante Giovanni Brown thought 'QDJ' was just a nickname, a one-off of Queen Latifah.

She didn't realize she was, literally, a queen (of the Jabari tribe, named for my dear friend and monster R&B producer Bari Taylor). Many of us don't know our own heritage, where we came from, who we are descended from. Queenie represented that journey of discovery, and she was also there to draw out Panther's humanity.

A brilliant stroke, thank you Sal Velluto, was his depiction of Ororo Munroe (Storm) as a child - drawing her to look exactly like Queenie. It was a nice touch and added value to the Panther-Queenie relationship. He's known Ororo all his life; QDJ reminds him of his great passion.

Oh, and wandering off-subject again: No offense to my good friend Reginald Hudlin, but the whole point of the T'Challa-Storm relationship, as I saw it, was they would never actually get together. It was an ages-long unconsummated love.

The worst thing a writer can do with a relationship like that is move toward the logical end because it ends everything that was interesting about the relationship. It buys you an event book and maybe a sales bump, but ends up causing more harm than good in terms of long-term characterization. When Jeannie married Major Nelson in I Dream of Jeannie, the series had nowhere to go.

Other than his mother, Ramonda, Storm is the only human being on the planet Panther cannot B.S. She sees right through him, knows him far too intimately.

Nrama: And what about the White Wolf?

Priest: Oh, that's easy: Kevin Spacey. His Southern Gentleman from Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil. Now much more obvious as the sinister, scene-chewing politico from House of Cards.

The White Wolf was (also obviously) the Black Panther's 'Reverse-Flash.' It seemed an obvious opportunity. My approach to Panther was always to have him defined by those around him (as opposed to Panther talking about himself).

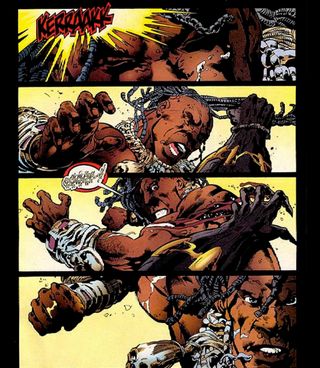

Nrama: Can you talk your depiction of Erik Killmonger?

Priest: I really liked Don McGregor's basic character design, but I wanted to explore a Wakandan native who'd been corrupted by western values. I believe T'Challa could speak English with a flawless American accent if he wanted to; I mean, if Hugh Laurie can do it, I'm sure Panther could. But he chooses to speak in (what I presume) is a lyrical and partially archaic speech pattern.

Erik doesn't mind being called 'Erik.' He eats at McDonald's. He wants Wakanda open for commerce and trade and is ready to open Wakanda-Disney. He is Black Panther without those pesky ethics. But he does, however, know all the tribal rules and knows how to use Parliamentary technicalities against the monarch.

Again, kudos to Sal and Bob for the brilliant full-issue battle between the two.

Nrama: And when did you find yourself realizing Black Panther was going to go on for a while?

Priest: When Marvel Editor Ruben Diaz called and yelled at me to get the script in for #13. I had assumed the book was canceled. I'd actually gone off to do something else when I got the call. I don't specifically recall why I thought the book had been canceled, but I did. The fact there actually was an #13 actually impressed me, that Marvel really was trying to make a go of this.

It was one of their best-reviewed and yet lowest selling books. Ironically, the run has gained in popularity after its demise, kind of like the original Star Trek TV show. It is favorably remembered and highly regarded, having won fans long after the fact.

I believe Reginald Hudlin's run is in large measure responsible for this, because he brought along a much bigger audience, many of whom later went back and read the old stuff as well.

And then there are mainstream fans who either weren't into comics at the time or who were skeptical about Panther - not (just) because he's Black, but because he'd been - no offense to any other writer - dull; the guy standing in the back row of the Avengers group photo. It'd be like giving Despero, from Justice League Task Force, his own book.

Only in a kind retrospect did the series grow more fans than it did when we were an active run.

I've actually had a recent discussion with Marvel about the possibility of returning to Panther in some fashion. Never say never, but I believe Marvel has graciously allowed me an incredible opportunity to say virtually everything I wanted to say about Panther. I'd hate to return to the character and the new stuff not hold up, and I'd hate to end up competing with myself.

I would, however, eagerly participate in a Milestone-branded Black Panther, but I'm sure that's unlikely to happen.

There's a host of exciting new writers who've energized comics over the past decade. It really is their turn to take us places and amaze us, and I'd love to see what ideas they have for this character and premise.

Nrama: Priest, let's talk about the storyline 'Enemy of the State,' which many claim is a high point of the character and your run.

Priest: I wanted to demonstrate how powerful, politically and militarily, Wakanda (nee Panther) is. From the beginning, I felt, 'This guy is a king. There ought to be political ramifications in here.'

Fans began calling Black Panther The West Wing of Marvel Comics. I'd never seen The West Wing and thus didn't catch the reference. I just love intrigue and complexity. I think most superhero stories have already been done a million times. I thought some manner of political showdown would be something new and different.

I also could not reconcile a sovereign king's desire to join a bunch of super-heroes. Panther is not, does not consider himself to be, a super-hero. It made absolutely no sense to me that he'd join the Avengers, a group he'd likely be suspicious of.

Which, then answered my own question: Panther joined the Avengers's because he was suspicious of them and, at least, wanted to be certain of their motives.

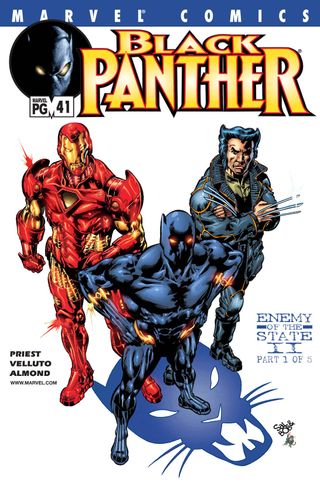

I think we actually did this geopolitical thing much better in 'Enemy of the State II'. I was on my knees begging editor Tom Brevoort to give me a shot at writing Iron Man, whose writing slot had come open. I didn't get the Iron Man gig, but Tom graciously allowed me to borrow the character, who became all but a permanent guest star in Black Panther for the story arc.

I'd whipped up some antipathy between Iron Man and Black Panther during 'Enemy of the State' that served 'Enemy of the State II' well, and it also occurred to me that there'd likely be some secret coffee klatch between the super-monarchs of the Marvel U, hence Magneto, Dr. Doom, Namor the Sub-Mariner, and, I think, the Lemurian king whatsisname meeting in 'Luke Charles' classroom. It was a big talking head scene, but it scored very well with the fans.

'Enemy of the State II' was on a much larger scale, involving Wolverine and Alpha Flight when Panther annexes Canada (Ha! Loved that) and takes over Star International with a single phone call.

I'm pretty sure my disappointment with Marvel at telling me they had no plans (years ago) to collect this stuff hit hardest on 'Enemy of the State II,' which I considered a high point of the series.

Nrama: And let's talk about the odd circumstances of your losing the title character to your own book and the "Vin Diesel Panther" as you called him (whom I liked!).

Priest: Kasper Cole. No, I liked Kasper and re-cast him as the White Tiger for the (gets angry every time he mentions it) series called The Crew, which Marvel canceled before the first issue shipped. The Crew was supposed to be akin to a Marvel version of Milestone: a book developed specifically for Latino and African American markets with some effort made to move beyond the normal comics distribution chains.

But, for some reason, Marvel later opted to include The Crew in a company-wide 'event' launch of several new titles. The Crew, which had simply breathtaking art by Joe Bennett, had absolutely nothing to do with that event concept, but when the new wave 'event' books were poorly received in preorders, Marvel slashed and burned, canceling several of the new titles and canceling The Crew as well, essentially killing it in its crib.

Which was when I pretty much quit comics. The development process was so difficult, the bar set so high, the hill so steep, weeks and months of agonizing rewrites and redos and begging, pleading, only to cancel the book before it ever had a chance to earn an audience. It's worth stressing none of this was the fault of Marvel editorial, it was a bean counter thing, but for me, it was an enormous punch in the face.

Absolutely no effort was made to move beyond normal (distribution) chains; they just sort of tossed it out there in this wave/event thing my book had absolutely nothing to do with.

If Marvel ever wants to get serious about penetrating the multi-billion-dollar Latino and African American markets, they should put out a The Crew trade and, more than that, explore additional marketing channels to get it to the right audience.

Back to Kasper...

I got a call from Marvel saying, "We've got this great idea: we're going to move T'Challa out and replace him with some young guy." To them, that would somehow fix the perception problem and boost Panther's sales. They were also going to move Sal Velluto, one of the most brilliant classical draftsmen working in the business, out and replace him with some Image-y guy.

I wasn't thrilled by the idea but was told, frankly, if I didn't go along, I'd be moved out as well. They'd just cancel the book and relaunch "Hipster" Panther with a new team.

This led to Kasper and the crime novel Black And White.

The "Image-y" artist never really appeared, though we had a really terrific artist to begin with, but he quit after the first issue. The remainder of this darker, hipper, more urban (i.e. 'Blacker') Black Panther was penciled by talented and well-meaning Latino artists who didn't know who P. Diddy was; who missed many of the urban nuances of the script and who really didn't know all that much about gangsta culture or, say, Brooklyn.

It was an incredible debacle. I worked very hard on scripts which, per Marvel's editorial direction, needed to be cutting-edge "street," but, despite the artists' best efforts, made no sense in print because they wouldn't know the design language of urban Black culture.

None of the artists could convey the BET/Gangsta Rap sensibility Marvel had requested; qualities Marvel insisted were missing from T'Challa Panther. The thinking seemed to be, if we made Black Panther more "street," it would sell better.

Which made no sense to me. It seemed, to me, like a group of white guys sitting around a conference room going [Eddie Murphy 'White Guy Voice'] "Don'tcha think Panther needs to be more 'street'? Tell Priest to 'Street' Panther up. Y'know--get more jiggy with it. The New 'Mo' Jiggy' Panther. The Even Blacker Panther, now featuring Vin Diesel."

Which missed the point T'Challa was not African American. He was African. T'Challa doesn't listen to hip-hop music or wear a Starter cap tilted on its side.

Against my better judgment, I gave Marvel exactly what they asked for, and then, incredibly, they assigned the art to several guys who were talented draftsmen but who were about as far removed from the streets of East New York as is galactically possible. Why not sign Jonas Kaufmann to sing Nicki Minaj tunes.

And the book got canceled anyway.

Which led me to Captain America and the Falcon, which got canceled, and then The Crew, which got canceled, and then to writing novels for iBooks/Simon & Schuster, which pretty much ruined me for comics because writing prose was so much fun (and freeing), and I didn't have to worry about the dozen other guys working on the project.

Nrama: The Black Panther's due to get major exposure with the upcoming movie, and I was curious as to your thoughts on that film, and Chadwick Boseman's casting as T'Challa.

Priest: I saw Get On Up about a dozen times. I went every day. Every single day, I was standing outside when the movie theatre opened and bought my ticket. The theatre was usually empty. I live in a town that wasn't eager or very interested in a James Brown biopic, but I couldn't stop watching Boseman.

I'm old enough to remember seeing James Brown live. Other than Boseman being too tall and skinnier than the real thing, his performance was utterly mesmerizing--and just as likely ignored because, honestly, James Brown never crossed over the way Ray Charles did, so Get On Up worked a more narrow vein of the American public than did Jamie Foxx's brilliant Ray.

I'm less concerned about Boseman's acting ability than I am about Marvel's understanding of the African American public and just how important a film this will be to us. In conversations with the Black Panther movie folk (and, it's worth noting the exec in charge of the Panther film is African American), I was left somewhat less at ease with their general approach that Panther will be essentially just another super-hero movie.

They know how to do these things, now, and nobody does superhero films better, but I'm worried about a certain level of hubris accompanying their approach to Panther.

I hope Marvel understands this: all of Black America is watching you. We are hopeful, we are excited. Don't screw this up. Talk to some actual Black people; it's not enough to "know" Panther; you've got to know Panther's audience.

It is also a mistake to not intrinsically understand how strong this racism thing is and how racism will - I assure you - impact this film's reception. The problem with most liberals - myself included - is we tend to think we're post-racial, that we've got a handle on things because we're not racists.

Which is what makes liberals perhaps some of the most pernicious racists of all, because we are in denial of it. Make a good movie, and people will come see it. Well, Get On Up was an extremely entertaining film with an amazing, practically one-man performance by Chadwick Boseman. But I was sitting in the theatre alone.

Memo to Marvel: Hubris and arrogance re: Panther will kill you. This is not like any other movie you've ever done. If done correctly, this can not only be a great superhero movie, but it could be an important film.

I'm not on the inside, so I can just pray they're not just trying to make a good movie but that they are trying to develop some sensitivity to the unique challenges their marketing will face. If they are tone-deaf to those issues, it won't matter how good the film is; there will remain a thread of resistance on the part of general audiences to seeing any film with a black actor at the center.

Nrama: Back to your run on the comic book series, any plans for the character you didn't get to do that you might like to share?

Priest: No. I put Black Panther in outer space. I think we jumped the shark with that one. The only thing I suppose I'd like to do is work on the character in a less creatively compromised environment.

I think, despite their best efforts, both DC and Marvel are simply not capable of delivering African American-themed products that pass the smell test within the African American community. I believe they both want to, I believe they're making strides and trying like hell.

I've been working on a screenplay called Isatai's Ghost for nearly 20 years. I doubt I'll ever finish it. It's a perfectly fine story, set at the turn of the century, but it involves Native American culture, Wounded Knee, and the virtual genocide of indigenous tribes set against a revenge motif.

The problem: my screenplay is too phony. I need to raise money to go meet people, live with people, really understand this culture and genre from the inside out. What I have so far is a result-oriented screenplay that may be entertaining on its face but does not breathe authentic air.

That, to me, represents the overwhelming majority of (specifically) African American themes and characters coming out of DC and Marvel, including the flat performances of the Falcon and War Machine in the film universe. These are entertaining performances on their face, but are emotionally hollow and lack meaningful impact.

Black characters in comics have traditionally been result-oriented products; writers sitting down, cracking their knuckles, "I'm going to write a Black guy wrongly sentenced to prison who gains super-powers and breaks out."

But, how well do these writers understand any of that? How many black friends do they have and how often do they hang out with them? How many times have they themselves been pulled over by cops for absolutely no reason?

I think Isatai's Ghost has a pretty decent plotline, but the screenplay is stillborn and possibly insulting to Native Americans, so it sits in a drawer until I'm more confident I know what I'm talking about.

To the best of my knowledge, neither DC nor Marvel has actual black people in executive positions. They're just out there kind of guessing, focus-grouping, asking people, 'What do you think of this...?' 'Will Black fans like that?'

The difference between that and, say, a shop like Milestone, is Milestone will not have the speed bump of being either racially over-sensitive or culturally distant from the pulse of the exploding urban minority market.

A Milestone editor will know who Sean Combs is and what his latest nickname is (I think he's just plain Diddy at this writing); will know is the fashion trends, the cultural trends. There'll be less guessing. Not because the Milestone editor is black (he may not be), but because this is what that shop does; this is the market that shop operates in.

If the major publishers were serious about the multi-billion dollar Latino and African American markets, they'd hire some actual Black people or, at least, come to terms with the nuances of creating product that will have actual credibility with the market they intend to penetrate.

So far as I can see, these are things they simply will not do, nor will they outsource it to a shop that actually does. Instead, these folks - good people, not demonizing anybody - sit around a table and guess. It's an incredibly dysfunctional and counterintuitive approach to publishing.

Film critics loathe Tyler Perry. But Tyler Perry films have no empty seats in the theatre. He understands not only his genre but his market, and the return on his films is higher than even some of Hollywood's biggest blockbusters.

I'd be intrigued to develop the Falcon or Black Panther or Jack Kirby's Black Racer or whomever out of a shop that better understood the genre and the market. None of which makes either Marvel or DC bad places to work. I'm just saying, among the many reasons Black characters don't sell as well as white characters is a fundamentally misaligned approach to both the genre and the market.

Make sure you've read all the best Black Panther stories of all time.

Zack is a comics journalist, who has written primarily for Newsarama, GamesRadar, and Indy Week. His words have also appeared in The Washington Post, AXS, VOX, The Sports Network, Gambit, and more.