BioShock: The Collection looks like you always thought it did, but it isn’t the shooter you remember

Your gaming memory always runs at 1080/60. Nostalgia is invariably well optimised. It doesn’t matter how old the game, how fuzzy the pixels, or however much the frame-rate juddered like a jalopy on cobbles. If you loved the game, your brain will always be playing the remaster. And that’s what makes real-life remasters such a tricky proposition. The developers can rework as much as they like, fine tune as many visuals, and smooth out as many kinks as can be found, but their efforts will always be battling with the false perfection already imbued upon the game by your mind.

That truth becomes immediately apparent upon playing BioShock: The Collection at Gamescom 2016. The pre-demo spiel is exciting. BioShock and its first direct sequel have been tuned up to the holy grail of pixels and frames. Textures have been up-resed. Character models have been improved and replaced where necessary. ‘Holy hell, this is going to look great’, says my brain. And objectively, when viewed side-by-side with the actual original games, it does. But unfortunately, that very same brain is not comparing The Collection to the actual originals, but to the made-up remaster it’s been quietly working on for nine years.

But on the flipside, knowing this means that my self-deluding lack of monocle-popping awe is actually a testament to the quality of the job that has been done. If a remaster is indistinguishable from the version in one’s stupid, rose-tinted brain, then it is a good remaster indeed.

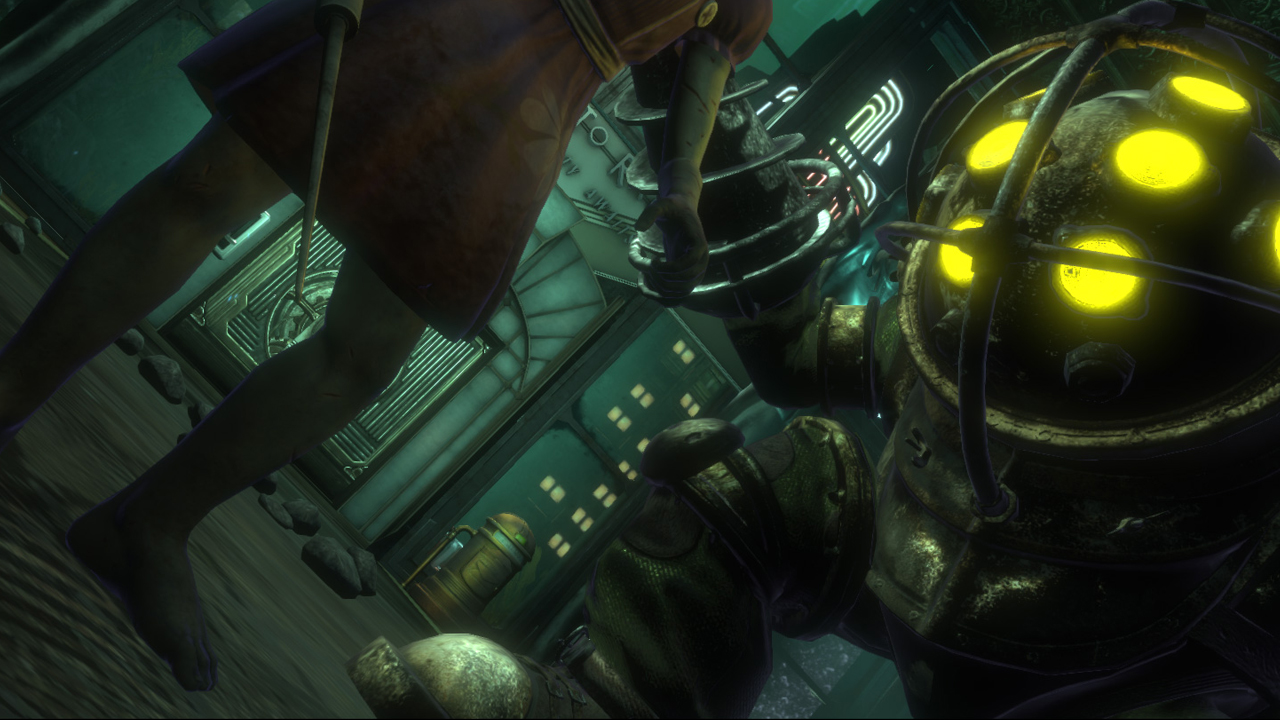

Actually, it’s not entirely true that BioShock: The Collection looks exactly the same as the mind’s eye version. Go looking for the improvements, and you will find them. The geometry of Rapture’s buildings is sharper and more distinct in the murk of the Atlantic. The Splicers’ nightmarish, mannequin rictus grins are even more unsettling now that the edges and shadows of BioShock’s chunky, stylised art are better defined. In fact, in that regard, there’s an interesting tangential effect throughout. With its artistic abstraction now presented more clearly, the feel of Rapture has changed slightly.

While the world feels a little more tactile, and player presence a little more robust now that everything’s running more smoothly, the fabric of Rapture feels a little more dreamlike, more unreal. Rapture was always a fantastic ghost train, but while increased awareness of its stylisation feels a little jarring at first, this slightly amplified sensitivity to the game’s aesthetic artifice eventually makes it feel, if anything, a tad more uneasy. Especially when those Spider Splicers are hurtling around the ceiling at 60 frames-per-second.

One area that definitely feels different upon a revisit though, is BioShock’s combat. It’s no secret that the first game’s strength never lay in the quality of its shooty-bang contingent. It didn’t matter at the time, because there was so much more going on, so much depth and complexity – both in the game’s narrative and in its dynamic, emergent, systems-driven world – that a whole generation of players who missed out on System Shock, Deus Ex and Thief the first time around were over-awed by the sheer amount of ideas at play. And justifiably so. But with familiarity and nearly a decade of FPS evolution bedding in since 2007, it’s now rather clear that BioShock’s gunplay – with its rigid control and distinctly underplayed feedback - is functional rather than fun in its own right.

But that’s okay. Because jumping a little further into the game – by way of the multiple save points 2K has conveniently left on my machine – rationalises things with rather more clarity. You wouldn’t notice it so much when playing through the game for the first time in a linear fashion, weapons and abilities steadily stacking up, and complementary, symbiotic strategies slowly emerging and branching. But jumping straight from ‘Electro Bolt and pistol’ to ‘Shotgun with incendiary rounds, chemical thrower with three types of ammo, stealth crossbow with electric snare-cable arrows, and five completely different offensive Plasmids’, the shift in the game’s focus becomes remarkably obvious. The game’s real intent becomes obvious.

Sign up to the 12DOVE Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

BioShock was never really an FPS. It was never supposed to be.

Perhaps the shooter-dominated landscape of the original game’s launch year confused us. Perhaps we were just lumping every first-person game into the FPS camp back then. That would be understandable, because all of this occurred long before the re-rise of the ‘immersive sim’ action-RPG. There was no new Hitman back then. There was no Dishonored, or Human Revolution. BioShock was the first game to start the resurrection. It was the first one to wave the flag that started the race to where we are now. So of course we didn’t quite define it properly. Of course we saw it as a horror shooter with cool other bits, rather than an immersive, reactive, RPG world that just happened to have a bunch of guns in it if you fancied the full-frontal attack option.

And of course BioShock’s true nature is obvious today, now that everyone is used to the sight of Corvo stopping time, teleporting about, rewiring a Tesla coil, and possessing a few fish in order to drop a room full of guards in less than half a second. Of course it’s clear, leaping straight from ‘Welcome to Rapture’ to Fort Frolic, that the latter area is where BioShock is really BioShock. Of course this game isn’t really a shooter, but is actually about surveying your surroundings, and setting traps, and scurrying from turret, to security scanner, to flying turret. Of course it’s about hacking each device’s loyalty at exactly the right time to catch your prey, as your pre-loaded booby traps – be they petrol pool, lightning cable, or otherwise – soften and herd it to your designated kill-zones without you needing to fire a single direct shot.

Of course that first, face-to-face-to-shotgun-to-face fight with a Big Daddy is, in truth, really there to display the unfortunate beasts’ immediate, close-range power, showing you precisely how not to fight them. Of course it’s entirely deliberate that your first big kill in the game comes about as a result of combining water, electricity, and a wrench. Of course the shooting is lacklustre. It was never really the point.

That doesn’t excuse the fact that those who do like shooting won’t find a great deal of instant gratification here, and I’m certainly not going to go as far as to infer that the chuggy, lazy aiming was ever a deliberate move to push players to more creative options. But it does make BioShock’s priorities clear. And that offers a tantalising tease of the real fun that lies ahead later in the campaign. A sharp reminder of why we all ended up loving BioShock, whatever kind of action we initially started playing it for.

So the really exciting question is, how will BioShock’s real game stack up when we revisit it after the followers whose path it paved? Will we see it differently? Will we play it differently, now more informed as to – and practiced in - its intended genre? And while BioShock will always be one of the best games of its generation – and almost certainly the most important – will its crown be tarnished by age and usurpers, regardless of how fresh the version in The Collection still looks? It’s an interesting proposition, and whatever the answer turns out to be, it’s certainly going to be a hell of a lot of fun to discover.

Most Popular