Battletech arcades were decades ahead of their time, holding global 3D matches before we'd even played a SNES - here's their story

We speak to the world's biggest collector, who owns 7 of the last 12 functioning machines

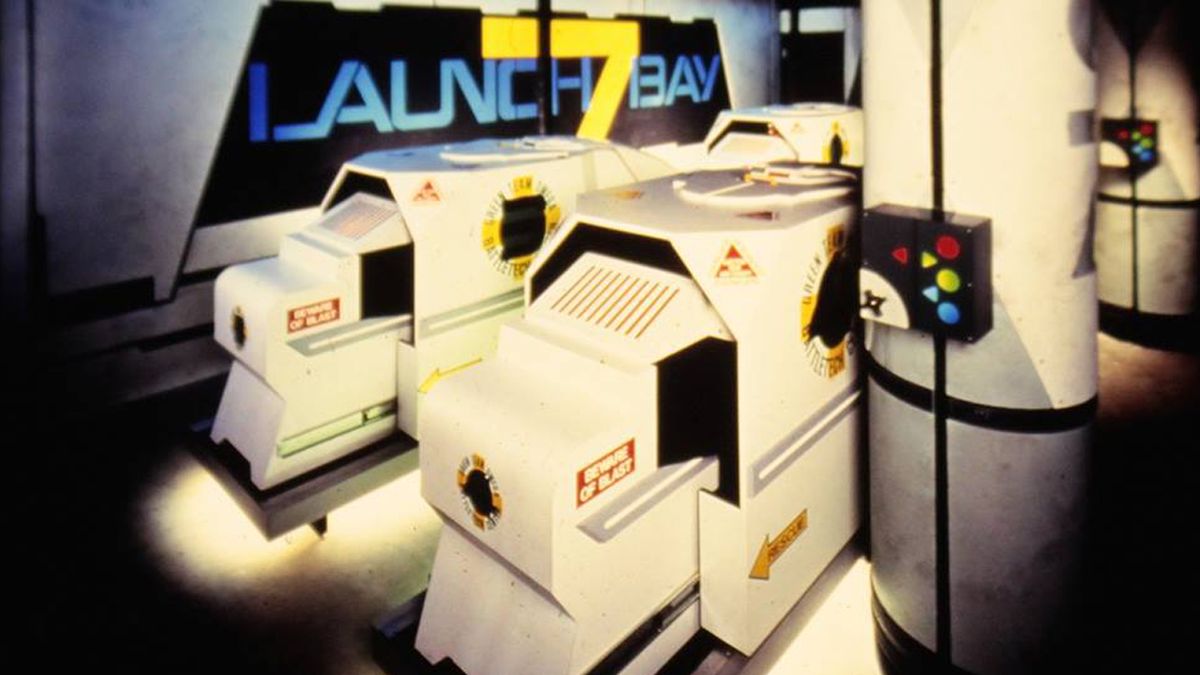

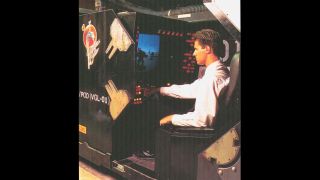

Imagine an arcade filled with rows of rectangular pods. As you climb into one and slide the door shut, the only illumination in the otherwise black interior comes from a huge monitor and a cornucopia of blinking buttons. In front of you there’s a joystick and throttle, along with two foot pedals. You’re in control of a 40-foot giant robot, and you’re about to enter into a deathmatch against other Mech pilots from across the world.

It sounds futuristic, but this is actually a scene from the early 1990s. You know it’s the nineties because Jim Belushi just gave you your mission briefing.

BattleTech Centers, later renamed as Virtual Worlds, were impossibly, almost comically ahead of their time. The first one opened in Chicago in 1990, promising 3D, multiplayer deathmatches at a time when the Super NES hadn’t even been released in the United States and Doom was just a twinkle in John Romero’s eye. The graphics of the generation 1.0 machines may look horribly dated by today’s standards, but they were stunning for the time - remember that most people were still playing on 8-bit consoles. And the elaborately detailed BattleTech pods were like something from science fiction.

BattleTech was huge in the 1990s, particularly in the US. It started off in 1984 as a board game created by by Jordan Weisman and L. Ross Babcock III, and inspired by figurines from the Japanese mecha franchise Macross. It was originally called BattleDroids until LucasFilm stepped in to lay claim to the word ‘droids’. The game had you duking it out with giant BattleMechs on a hexagonal grid, rolling dice to deal damage, and it quickly spawned a host of spin-off media, including more than 100 novels and the MechWarrior series of PC games.

The fact that something as insanely ambitious and expensive as the BattleTech Centers got off the ground at all is a testament to the caché of the BattleTech brand. And BattleTech Centers, soon redubbed as Virtual Worlds, quickly spread across the United States and beyond. A total of 26 sites opened in Japan, Australia, the Trocadero arcade in London and several major US cities.

“A really cool environment”

Michael, a BattleTech collector from Texas, fondly remembers the opening of the Dallas Virtual World in 1994. “I went there as often as I could when I was in college. I probably played 500 or 600 games during the time the site was open. It was a really cool, fun environment - we’d bring up board games and play them there, and they also had message boards where you could talk with players at the other sites. I’ve made friends there that I’m still in touch with now.”

The BattleTech machines were hardly cheap - it was $7 for one play, which is nearly $12 in today’s money when adjusted for inflation. That got you about 10 minutes, after which there was a mission review where you received a printed scoresheet so you could compare your performance with your friends. Michael says he still has some of his first scoresheets as mementos.

Sign up to the 12DOVE Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

The pods may have been expensive, but the price reflected just how cutting-edge the technology was. You could play against several different opponents at a time, even if they were at other sites across the world - and bear in mind that this was at a time when the internet was hardly even a thing. Michael recalls that the latency was pretty poor, since the sitelink was built on ISDN, but “just the experience of playing against someone in Japan was worth the lag”.

Players had a choice of two games, BattleTech: Firestorm or Red Planet. The former saw pilots gunning each other down in giant mechs straight from the BattleTech universe, and it was the game that initially hooked Michael. But the ‘Martian Football’ mode of Red Planet ended up being the game he played the most.

Red Planet, which is unconnected with the BattleTech universe, features hover cars racing at impossible speeds through tunnels and valleys on the surface of Mars. And it has a truly amazing tutorial video featuring the likes of Judge Reinhold, Weird Al Yankovic and Joan Severance, who played the villain in the Gene Wilder and Richard Pryor comedy See No Evil, Hear No Evil.

The game has several modes, and Martian Football is a bit like an early Rocket League, but with American football instead of soccer. One player is the ‘Runner’ - or the ball, if you will - and teams of ‘Crushers’ chase after their car with the aim of knocking it out of play. Meanwhile, ‘Blockers’ attempt to protect the Runner by heading off the Crushers. Michael reckons that over the years he’s played in BattleTech pods 20,000 to 30,000 times, and the vast majority of those games have been Martian Football.

The rocky road to retro

The Dallas Virtual World closed in 1996, which Michael puts down to over expansion and the company stretching itself thin - the pods were expensive to play and maintain, and each cluster required an attendant to help players get set up. But the story doesn’t end there - Virtual World teamed up with Dave & Busters to install pods at its restaurant and entertainment complexes across the US. And in 1996, Virtual World launched the Tesla pod, which was a considerable improvement on the generation 3.0 pods it replaced. The Tesla pods, and the Tesla II pods that superseded them, had a whopping seven monitors, along with dozens and dozens of functional buttons and a swanky new curved design. The simulation feel was comprehensive - players had to manage every aspect of their BattleMechs, right down to monitoring heat output.

But eventually, in 2005, Dave & Busters decided to get rid of its Tesla II pods - Michael thinks it was because the chain wanted to get away from “attendant-based attractions”. All of the pods were put up for sale, with most being snapped up by enthusiasts and arcade chains. Some still operate today: for example, the MechCorps group owns a phalanx of pods that they take to gaming conventions, and so does The Fallout Shelter Arcade in Minnesota.

By this point, Michael was a pod addict. He travelled to three Red Planet competitions a year in New York and Cincinnati, events that attracted competitors from as far away as Japan, and was an avid collector of BattleTech jackets and ephemera – even buying a six-feet-long model of an Atlas BattleMech fist, which he keeps in a lock-up outside Dallas. He also has a three-feet-long model of the Vester Thrust Vehicle from Red Planet that he picked up for $200.

He already owned eight working generation 3.0 pods, and bought another ten Tesla II pods after Dave & Busters sold off their inventory. The 3.0 pods in particular are incredibly rare now. Michael reckons that there are only around 24 left in the world - but only about 12 of them still work, including his eight. He has two of the 3.0 pods set up in his garage, while the rest are in storage along with that massive robot fist. But owing to the searing Texas heat, he reckons it’s too hot to enter the garage and actually play on the pods for about eight months of the year.

His aim is to get all of his BattleTech pods fully refurbished and set up in an arcade somewhere - but finding a suitable location has proven difficult, mostly because the machines are so big. “Arcades that were interested didn’t have space, and those that had space weren’t interested,” he says.

The other problem is that it’s becoming increasingly hard to maintain these ageing machines. The Tesla pods aren’t too bad, he notes: “It’s the same components you’d find in any arcade machine. They basically just run on Windows PCs.” But the older 3.0 pods are a different story. “They have two pre-VGA CRT monitors, which are very hard to get hold of now. And they use a proprietary card that loads all of the software. I have three cards, and there may be three more in existence - but once they fail, they’re just expensive paperweights.”

Future war

Michael is still hoping he can find somewhere that might host his pod collection - he reckons there’s a chance that a bowling alley somewhere might take them. It would certainly be a crying shame if these important artefacts of gaming history were left to rot in a storage unit.

These fantastical machines were clearly far ahead of their time back in the early 1990s. Indeed, they were featured on the Discovery Channel’s Beyond 2000 TV programme back in 1992, when the awed presenter declared: “This new video sport is expected to spread wherever science fiction buffs have the money and the inclination to become part of this fantasy.”

Well, money ultimately proved to be the sticking point. Greg Corson, who worked as a software programmer at Virtual World Entertainment for seven years, recalls that the first wave of pods were horrendously expensive, partly because they used proprietary components. “I think Virtual World Entertainment was just a little too far ahead of its time when we started, making many of the things we wanted to do too expensive to be practical.” The later, more advanced Tesla pods used off-the-shelf parts, so they were actually cheaper to make. And Greg reckons that producing something similar nowadays would be even cheaper: “Today, with the improvements in development tools and huge drops in computer costs we're seeing the overall cost of developing/running this kind of business would be less than half what it was in 1990, making it a practical business.”

With the rise of esports worldwide and the creation of dedicated gaming arenas like Belong in GAME stores, perhaps now the time is right for the BattleTech pods to reemerge in a new form - especially as two new BattleTech games are scheduled to be released in 2018, potentially rekindling interest in the franchise.

But for Michael, it’s also important to preserve the past, and the game that became so important to his life. “It’s turned into lifelong friendships,” he says. “I’ve made friends all over the world, from Japan to other cities in the US. It’s been such a great experience - and that’s why I’m motivated to preserve the pods and keep them going.”

In the mood for retro? Check this out: Do you prefer your nostalgia Hotline Miami or Contra-flavored? Two upcoming 2D shooters are here to satisfy

Lewis Packwood loves video games. He loves video games so much he has dedicated a lot of his life to writing about them, for publications like 12DOVE, PC Gamer, Kotaku UK, Retro Gamer, Edge magazine, and others. He does have other interests too though, such as covering technology and film, and he still finds the time to copy-edit science journals and books. And host podcasts… Listen, Lewis is one busy freelance journalist!

Actors supporting AI protections didn't know they were being replaced in Zenless Zone Zero update 1.6: "I found out the role was recast today alongside all of you"

Ubisoft shareholder plans protest in response to mismanagement, Assassin's Creed Shadows delays, and alleged acquisition talks with Microsoft and EA