Why you can trust 12DOVE

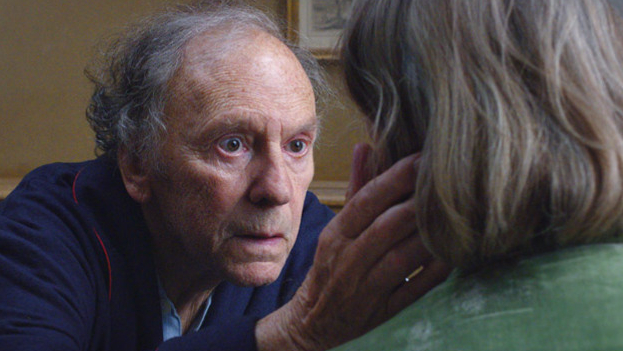

Old age and terminal illness are placed under Michael Haneke’s microscope in Amour .

But far from being a cold, scientific study from a filmmaker frequently accused of placing a pane of glass between his work and his viewers, this sensitive film emerges heartfelt and humane.

Opening with the police breaking down the doors of a Parisian apartment to find the corpse of an old woman laid out in bed, the Austrian auteur then takes us through the months leading up to this discovery.

Octogenarian couple Anne and Georges (Emmanuelle Riva, Jean-Louis Trintignant) share a tender, attentive relationship. Then Anne suffers two strokes and the film records, unflinchingly, her incremental demise.

In evidence, always, is the love of the title (a love far more profound than the honeymoon fervour portrayed in most movies), Georges feeding her, washing her and attending to her toiletry needs.

But present also is the humiliation of debilitation.

Shame, fear, despair frustration... all clog the apartment and provoke an overwhelming sense of suffocation, while an all-too-human loss of patience proves utterly shocking - as cruel and devastating as anything in Haneke’s back catalogue.

Contained almost entirely within the couple’s elegant apartment, Amour comprises static takes, softly, somberly lit, and the odd track or pan to freshen the frame.

Controlled but never cold, it eschews music to underline the complex emotions at play, instead trusting in Riva and Trintignant’s tremendously skilled performances.

Watching Georges struggle to make Anne’s deterioration bearable as she, all the while, desperately craves release (“Why should I inflict any more pain on us?”), we’re forced to confront some terrible questions.

How to cope with losing a soulmate? How far do courage and integrity stretch, and to what end? Is a life like this even worth living?

Amour contains its share of caustic confrontations, with the exchanges between Georges and a house nurse (Carole Franck), and between Georges and his daughter (Isabelle Huppert), worthy of Bergman’s domestic dramas.

But, for the most part, fighting death is enough. In place of Haneke’s signature nihilism and austerity come warmth, nobility and, yes, love. The drama scars all the deeper for it.

Jamie Graham is the Editor-at-Large of Total Film magazine. You'll likely find them around these parts reviewing the biggest films on the planet and speaking to some of the biggest stars in the business – that's just what Jamie does. Jamie has also written for outlets like SFX and the Sunday Times Culture, and appeared on podcasts exploring the wondrous worlds of occult and horror.

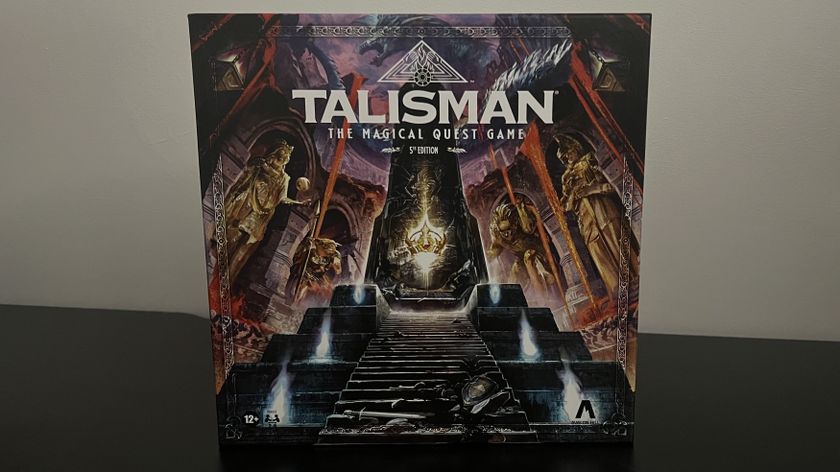

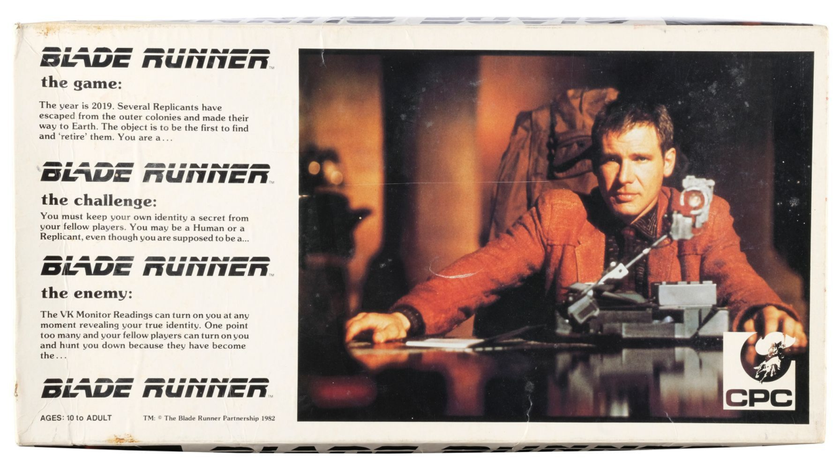

Rare Blade Runner board game prototype is being auctioned for over $500 but there’s a far cheaper way to bring the neo-noir classic to your tabletop

Scarlett Johansson doubles down on never coming back as Black Widow: “Natasha is dead. She is dead. She’s dead. Okay?"

Lenovo Legion Go S Windows 11 review: “my heart aches for this mixed up handheld”