9 fan theories that make good movies better, and bad ones bearable

With dozens, if not hundreds, of people involved in the average production, film is possibly the most collaborative medium around. But the collaboration doesn’t always stop when the film is finished. Sometimes the audience gets involved too. Sometimes, the viewer continues to rework a film via creative reinterpretations of plot-points, and the imaginative discovery of events and character motivations not explicitly apparent in the original work.

At their best, these head-canon theories make great films fantastic. At the very least, they’re capable of making bad ones more interesting. The internet is brimming with them, but I’ve pulled together the best of the best below. You’ll never watch Titanic in the same way again.

The Rock (1996)

The theory: It’s a Bond movie

In The Rock, Sean Connery plays John Mason, the only man to escape from Alcatraz. In fact, he’s so good at the whole covert business that he escaped from the notoriously inescapable island prison just one year after being incarcerated. But there are more interesting details to his character. Much, much more interesting details.

During the film, we’re told that he’s a lethal trained killer. We’re told that he was trained by British intelligence, with a fair bit of that coming from the SAS. We’re told that he was caught and imprisoned some time in the ‘60s, after spying on the US for years. We’re told that he officially doesn’t even exist.

James Bond is an ex-SAS, British intelligence operative. He’s had an uneasy friendship with US intelligence for years. Connery’s Bond was at his peak in the ‘60s. And, if you buy into the biggest Bond fan theory of all time – which claims that ‘James Bond’ is a codename given to any current 007, allowing for all casting changes to be canon, while also explaining the strange continuity of Judi Dench’s M between Pierce Brosnan’s Bond and Daniel Craig’s ambiguously rebooted one – then the description of Mason as not technically existing makes all kinds of sense.

And the best bit? At one point in The Rock, Mason responds to an introduction by Nicolas Cage’s Stanley Goodspeed with the line: “Of course you are”. A line Connery first used upon meeting Lana Wood’s Plenty O’Toole in Diamonds Are Forever.

Sign up for the Total Film Newsletter

Bringing all the latest movie news, features, and reviews to your inbox

Ghostbusters 2 (1989)

The Theory: The whole film is set in purgatory

If you watch the DVD commentary for the original Ghostbusters, you’ll learn that the huge explosion that occurs when the boys in grey cross the streams to destroy the Stay-Puft marshmallow man was intended as a joke. It’s massive, like a small nuke going off at their feet. There’s no way they could have survived. But they do. But what if they hadn’t? What if that clean – apart from the marshmallow - ending seemed implausible because it was? What if Ghostbusters doesn’t end how we think it does at all?

It would certainly explain a few things about Ghostbusters 2. Because while brilliant – and one of the best Christmas films ever made – the film does have a few structural niggles. Namely the way that it jumps through hoops to repeat the same plot structure as the first movie. The guys are once again down and out, and almost entirely discredited. Peter is once again single and chasing Dana, with slim signs of success. No-one believes in ghosts again. After very conspicuously saving the world from apocalyptic supernatural threat a few years earlier, little of this is plausible.

Unless Ghostbusters 2 is not set in corporeal New York, but actually depicts the Ghostbusters in some sort of purgatory, doomed to repeat their actions indefinitely until they can make it out. Maybe they died at the end of the first film. Maybe they caused a cross-dimensional rip and were pulled into Somewhere Else Entirely. Maybe Gozer quickly yanked them into a limbo dimension of its own making. Or maybe a limbo of the guys’ own unconscious making, given how that whole ‘Choose the form of the Destructor’ thing worked.

Vindicated by a moderate-scale bust in a very public location – the Scoleri Brothers in the courtroom as opposed to Slimer in the Sedgewick Hotel? Check. Immediate celebrity, success-montage, then the discovery of an ancient evil at a significant New York landmark? That happens again too. A climax in which a huge, humanoid entity walks the streets of the city? Yep, we get a repeat of that as well, only this time, Big Stompy is on the good guys' side.

And it makes sense for each of them on an individual level too. Peter gets a second chance to woo Dana, this time with the bonus of being able to settle down as a family man. Egon sees Janine happy with someone else, after awkwardly fielding her affections for most of the first film. Ray gets to exorcise his marshmallow guilt-demons, using the Statue of Liberty to symbolically subvert the whole Stay-Puft incident. All four of them are ultimately saved by a New York crowd singing Auld Lang Syne, an obvious antidote to the previous, public doubt they’ve suffered, with a really heavy subtext of letting bygones be bygones. And Winston? Okay Winston doesn’t really get to do much, but he didn’t get to do much in the first film either. Ernie Hudson really got dicked by the script edits on that one.

Kill Bill (2003/2004)

The Theory: It’s a movie within a movie

Kill Bill represents a definite tonal change for Quentin Tarantino. Where his first three feature films – Reservoir Dogs, Pulp Fiction, and Jackie Brown – played around with genre tropes and conventions, but nevertheless delivered gritty, grounded, ‘real-world’ movies, albeit with notable stylisation, Tarantino’s martial arts love letter plays out like a gaudy, cinematic theme park. It’s great, of course, but between the many visual gimmicks, the deliberately retro shooting and editing techniques, and a whole bunch of drastic switch-ups in audio-visual tone, there’s a severe step-up in deliberately cartoonish, movie-making artifice. Literally, in fact. There’s an entire anime section. Just because anime.

But there’s a fan theory that makes sense of all of this, while also tying Kill Bill back into Tarantino’s connected movie universe in the most quintessentially Tarantino way possible. The theory is that Kill Bill is not just a movie in the real world, but also within the movie world. As in, there could have been a copy of it lying around in Butch’s apartment in Pulp Fiction, or in any video store in Jackie Brown.

Even better, there’s a chance that Kill Bill could be related to a TV show specifically mentioned in Pulp Fiction. Remember Fox Force 5, the cheesy, all-female spy pilot that Mia Wallace starred in? It featured five women. Mia’s knife expert, a Japanese martial artist, a deadly blonde, an African-American, and a French agent. All five archetypes correspond directly to the five main female characters in Kill Bill, correlating to The Bride, O-Ren Ishii, Elle Driver, Vernita Green, and Sofie Fatale, respectively, all agents of Bill’s assassin cabal.

Fox Force 5 never made it to a series, but we know that ideas kick around Hollywood for years, getting remade, readapted, reworked and ripped off. So is Kill Bill a big-screen adaptation of the failed TV pilot? A gritty reboot? Another attempt at the franchise, rewritten by a new scribe – or several, given the way Hollywood script development usually goes? All are entirely possible. Probable, in fact. The credits might say that The Bride is played by Uma Thurman, but the truth of the matter might be that that’s actually an older Mia Wallace taking the lead.

The Descent (2005)

The theory: Most of it doesn’t happen, and there is no happy ending

The Descent is a bloody good horror film. As long as you watch the original, UK edit, that is. Otherwise it’s a bloody good horror film with an awful, out-of-nowhere, entirely discordant happy ending. Though on the bright side, while this next fan theory makes the original cut of the film lightly grimmer (or at least differently grim), it makes the happy funshine version decidedly darker.

The gist is this: Sarah is on a cave-diving trip with her friends, a year after the death of her husband and daughter. Along the way, the group stumbles into the wrong tunnel system, as well as a whole ‘civilisation’ of ghoulish cannibals, diverged from humanity in the distant past and now adapted to (savagely) survive underground. Naturally, a lot of people die. Everyone apart from Sarah dies, in fact. And as the heroine of the film, Sarah kills a fair number of monsters along the way.

But the interesting part is that Sarah is unambiguously suffering from severe PTSD following the accident that killed her family. She’s seen having horrific nightmares from the start of the film, and later, in the UK cut, hallucinating entirely. And the most interesting part? Sarah kills the exact same numbers of monsters as she has friends who die. So how about if there are no monsters? How about if they, and the scenario that plays out, are all a hallucination, spinning out of Sarah’s understandably disturbed mental state, perhaps her brain’s means of turning her pain into a tangible threat that she can fight back against? How about if those aren’t monsters she kills at all? Unsettling enough in the original version of the film, but in the US edit, she eventually makes it out of the caves and back into the real world, meaning that a delusional killer is on the loose, and liable to attack (and gratuitously stab) anyone she comes into contact with.

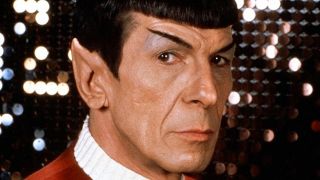

Star Trek 6: The Undiscovered Country (1991)

The theory: Spock is related to Sherlock Holmes (or Sir Arthur Conan Doyle)

In Star Trek 6: The Undiscovered Country, Spock drops the old Sherlock Holmes adage that “when you eliminate the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth”. The sticky bit? He prefaces this allusion with “An ancestor of mine maintained…”

So (logically) Spock must be either a distant descendant of Holmes, on his human mother’s side – which places Trek and Sherlock in the same universe – or related to Holmes author Sir Arthur Conan Doyle himself. Because it would be distinctly unlike Spock to be either a) wrong about the origin of the quote, or b) trolling. It’s more likely that Doyle himself is the ancestor, as Holmes is an unambiguously fictional character in Star Trek: The Next Generation, Data being famously obsessed with the literary figure.

Though an even more fun interpretation is that rather than there being an ancestor of Spock’s mother, Doyle was actually a Vulcan who found himself accidentally trapped on Earth, centuries before first contact officially happened. Hence his most famous character’s unusual intellect and legendary grasp of logical thinking.

Titanic (1997)

The theory: It’s canonical with The Terminator

Made of grand, romantic, historical sweep it may be, but you know what else Titanic is also full of? Clattering anachronisms.

Or are they? You see, most of these temporal trip-ups are notably centred around Jack. They start out innocently enough, with a few possibly excusable aesthetic points. His haircut, for instance, is way out of step for the period. It didn’t become popular until the late ‘30s, whereas Titanic is set in 1914, because that is when the actual Titanic sank, and so it kind of has to be. His rucksack, similarly, is modelled on a ‘30s Austrian military design. But then it gets weird.

You see, over the course of the film, Jack also references having seen and done things that just were not possible in 1914. He mentions having ice-fished at Lake Wissota, a man-made lake that was only dug in 1917. He offers to take Rose to ride the roller coaster at Santa Monica pier, which would be a challenge given that said roller coaster wouldn’t exist for another four years. All of this points to one conclusion.

Jack is a time traveller.

But why, with knowledge of the future, would he choose to be on the Titanic, of all ships? The obvious answer is that he’s there to save Rose. He saves her from suicide early on, and then pretty much refuses to leave her side. But this raises another big question. Why save one person when he could have saved the whole ship? Especially when, if Rose – a rich, white woman - had jumped off the vessel, the resulting stop-and-search might well have led the ship to miss the iceberg altogether. There must be a reason why Rose is so important. There must be a reason why her life was worth sacrificing those of over 1500 more. And there is a reason. Of course there’s a reason.

Rose is Sarah Connor’s grandmother, and Jack was there to maintain her bloodline. And like Kyle Reese, he might well have ended up siring part of it himself.

The Matrix trilogy (1999/2003)

The theory: There are two Matrixes

There’s the obvious, shiny buildings and physics-bending kung fu Matrix, and then there’s the entirely less exciting, emergency back-up Matrix of Zion and the Real World. If you become aware of the first, you get booted into the second, and you think you’ve won. But really all that’s happened is that you’ve been kicked from the game into the lobby. You’re still in the system, just in another, seemingly less active section of it.

Why is this a better interpretation of The Matrix? Because first of all, it makes the machines’ actions make a lot more sense. According to the films’ official line, supposedly hyper-intelligent AIs have had centuries of free evolution, and dedicated much of that time to the study of the human mind. They have apparently been aware of our ability to question – and leave – ‘reality’ for generations. They have modified the Matrix several times over in order to make it more palatable, rebooted it on multiple occasions of absolute disaster, and yet still have no better overall plan than ‘let the humans leak out, deal with shit only when it truly hits the fan’.

The original film gets away with it by keeping the scenario simpler, and leaving off with an open-ended finale. But the sequels? A train-wreck of narrative implausibility. As well as being just plain terrible.

But if the Real World is just another Matrix, it all makes complete sense. And the films discuss much more interesting questions about the nature of human acceptance, and our willingness to believe in the ideal and imperfect. Questions, in fact, that Agent Smith raises in one of the first film’s most important scenes, but which are then entirely ignored in the sequels. And we can finally, finally make sense of Neo’s ridiculous ability to use Matrix powers in the Real World, in Revolutions. Because otherwise that stuff is just plain stupid, however you look at it.

And that odd, tonally off-kilter, implausible cop-out truce at the end of the trilogy? It becomes a fantastic ending. Because there is no truce. Once again, the machines are just giving the humans what they want to believe, and keeping them unknowingly servile all over again, just like they always have.

Event Horizon (1997)

The theory: It’s set in the same universe as Warhammer 40,000

Event Horizon, Paul Anderson’s only legitimately great film, deals with the reappearance of a long-lost, experimental starship that vanished years previously after a cutting-edge warp drive test seemed to fail. In truth, the ship has been lost in another dimension. It may have been an untamed chaos dimension of traditional space. It may have been actual Hell. The latter may actually be the former. No-one knows for sure. But it doesn’t really matter either way. By the time it returns, the titular ship is all messed up, loads of people are dead, and a whole lot of madness and murder is on the way for all on board.

Now here’s the thing. The Warhammer 40,000 series of tabletop boardgames and associated spin-offs take place in one of the most notorious Crapsack Worlds in all of media. That’s 40K’s schtick. Being so relentlessly doom-laden, horrible, and hopeless that it’s downright hilarious. There is only war, there is only darkness, and there is only the chance to die in futility, in one of a thousand horrific ways. As a result, some of 40K’s tech is ludicrously unpleasant. And chiefly unpleasant are the workings of warp travel.

Following a similar model to that of Star Trek, only much, much bleaker, 40K’s interstellar travel uses traditional principles of taking shortcuts through space-time, in this case via wormholes. But 40K maintains that the actual Warp itself – that very plane outside of space-time which inherently has to be traversed on each and every long-distance journey - is, yes, a nightmare chaos dimension. Special preparations have to be made for every trip, in order to stop huge swathes of crew being lost, going mad, and dying horribly. It’s never 100% successful, and involves using fearful psychic mutants to navigate through the hellscape, but it’s better than just going in willy-nilly.

And thus, Event Horizon is a prequel to Warhammer 40K, set in a much more recognisable, near-future version of that far-future universe, at the point that mankind first accidentally stumbled upon the Warp, long before 40K got entirely messed up in every conceivable way.

I Heart Huckabees (2004)

The theory: It’s a sequel to Rushmore

Okay, here’s one of my personal favourites. And it’s not quite a fan theory, more a way of making two great films even better with a little creative reinterpretation. But bear with me on this one.

In Rushmore, Wes Anderson’s second film, Jason Schwarzman plays Max, an egotistical fantasist of great intelligence and ingenuity, with a total unwillingness to apply himself at school, and a seeming inability to relate to the truth of the real world, let alone deal with it. He lives in his fantasies, driven by his surreal, single-minded sense of self-belief. He alienates people, pushes away opportunities, and continues to fruitlessly push forward in the fictional, Max-ccentric world he has constructed for himself. By the end of the film he has started to realise his errors, and is making headway in building a healthier, more connected life for himself. But there’s still a slight air of ambiguity as to how long it will last.

Cut forward six years, to I Heart Huckabees, a technically unrelated film by David O. Russell. A now mid-20s Schwartzman plays Albert, a young man going through a crippling existential crisis, seeking the help of whimsical psychologists-cum-philosophers-cum-detectives Lily Tomlin and Dustin Hoffman in a bid to sort his life out. All well and good. A great film, in fact. But you know what makes it better? If you assume that Albert is Max, and I Heart Huckabees is a sequel to Rushmore.

He didn’t quite fix himself at the end of Anderson’s film, spiraled back into self-aggrandising fantasy, and now, after years of being forced to face the daily realities of life outside high school, his carefully constructed sense of self, and meticulously manufactured interpretation of the world, have started to fall apart. He doesn’t know what’s real anymore. He can’t understand how or why anything happens. His entire narrative for existence is under serious threat. And he needs help. "How am I not myself?" indeed. Honestly, watch the two back-to-back and you’ll see it. Even if you’ve seen both films already, you’ll see them entirely new if you run them as a double-bill.

Most Popular