32-bit graphics are the new retro

Video game nostalgia takes different forms for different people. We're well past the saturation point for 8-bit and 16-bit aesthetics in the indie scene, which strives to evoke fond memories of playing your NES in the living room or picking a side in those schoolyard debates of Super Nintendo vs. Sega Genesis/Mega Drive. But the gamers who grew up with those sprite-centric visual styles are getting older, and when your formative gaming memories revolve around the rudimentary 3D graphics of the fifth console generation - primarily the PlayStation, Sega Saturn, and Nintendo 64 - your personal vision of what defines 'retro' graphics is rarely used in contemporary games.

Fortunately, indie artist Charles Blanchard (known online as DelkoDuck) is keeping the 32-bit dream alive.

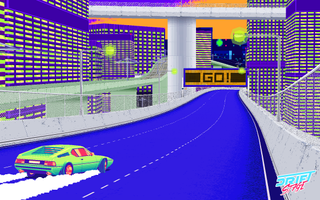

Blanchard is the lone artist on two nostalgia-touched indie games that channel the spirit of 32-bit gaming, with stark, visually striking graphics that use low-polygon models - the kind of blocky, simplistic designs that epitomized 3D graphics during the mid-to-late '90s. Sky Rogue is a brightly colored, procedurally generated reimagining of dogfighting classics like Ace Combat and After Burner, while Drift Stage offers neon-soaked arcade racing that combines the zippy, tire-burning turns of OutRun with the polygonal tracks of Daytona USA or Sega Rally Championship. Playing Sky Rogue or Drift Stage feels like uncovering a fifth-gen console treasure lost to time - one that strides straight out of 1994, but with the smooth controls and blazing-fast framerates made possible by modern-day computing.

Blanchard carefully studied and recreated the style after years of deconstructing and tinkering with it. There are actually multiple disciplines within the low-poly realm: Sky Rogue uses single-tone blocks to build everything, akin to the original Star Fox (a technique Blanchard calls "flatshaded"), while Drift Stage takes flat pixel art textures and wraps them around the 3D wireframes of cars ("sort of similar to making papercraft models," says Blanchard). The technical nitty-gritty is enough to make any non-artist's head spin, but the fundamentals work just as well now as they did back then. "All the techniques I use are old," says Blanchard. "It's stuff people used in the industry when they were working on PS1 games, and that whole era."

It's a process he's been working to perfect since as far back as middle school. "You could replace the textures in an N64 game using an emulator, and people did that on Ocarina of Time and stuff; they'd make things like HD texture packs," explains Blanchard. "I never made a full pack, but I would just mess around with it and make icons and shit, try and make [Ocarina] Link look like Link in Zelda 2, make his hair brown and stuff. Just from doing that, I would look at all of the dumped N64 textures, and I'd see how big they were, and how [the artists] cut up the UV maps. I sort've picked up some ideas from them, and I've since expanded on them... it's been an evolution, I guess." Blanchard would go on to share and sharpen his techniques as an avid member of the Polycount forum, a breeding ground for unique 3D art styles and tricks of the graphical trade.

Given the vast number of unconventional games in the 32-bit libraries, Blanchard and his fellow developers have plenty of design oddities and unique solutions to learn from. "The whole [Drift Stage] team sends each other videos of games; 'Look at the graphics in this one. Look what they did here,'" says Blanchard. "Mostly we're on Sega Saturn right now, because there's so many obscure games for it, and because that thing was so hard to program for... [the original developers] did weird things to get by with what they had."

The retro racer that the Drift Stage crew most reveres is Need for Speed 3: Hot Pursuit on PS1 ("I don't how they did it on the hardware back then - I actually looked up the team [so I could] email them and get some tips," laughs Blanchard). Thankfully, Blanchard and his team don't have to wrestle with hardware limitations, able to crank out 60fps with no sweat. They've experimented with purposely capping the framerate at 30fps to further emulate the graphical conditions of the old consoles, but as Blanchard puts it, "they wouldn't have stuck with it back then if they didn't have to, so now, we're just like 'Nah, fuck that.' Why downgrade ourselves?"

Sign up to the 12DOVE Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

When you're trying to line up a lock-in during aerial combat or pulling off a pristine drift through a hairpin turn, you may not even notice all the miniscule aesthetic details that make Blanchard's environments feel so authentic. The single, metropolitan-themed track currently available in the Drift Stage early alpha demo is essentially a highway floating between skyscrapers, supported by concrete pillars that gradually fade into a black void reminiscent of PS1-era draw distances. Getting the faraway city skyline to look just right in the vibrant, orange-and-purple skybox was an incredibly complex task involving parallax scrolling and projected textures, all to recreate that sensation of a surrounding that never seems to get closer, no matter how far you move in any direction. Drift Stage programmer Chase Petit had to write code for the express purpose of replicating the effect. "No one knew how to do it; there's no documentation, since it's such an outdated technique," laughs Blanchard.

And yet, all this effort to mimic the 32-bit style might be dismissed by those without an emotional attachment to fifth-gen-era graphics. Take the static, purposefully grainy ocean in Sky Rogue: "People tell me all the time that the water texture sucks," says Blanchard, "and I'm like, 'Uh, no it doesn't. If you think that sucks, you don't get why it's there.' I've had people say Drift Stage looks like it should cost 99 cents on the app store." Given the graphical fidelity of contemporary games, the jagged models and pixelated textures of the 32-bit era can look jarring, especially if you have no frame of reference for the bygone days of PS1 and Sega Saturn.

That said, low-poly art styles have been known to pay off with younger crowds, Minecraft being the dominant example. "I feel like Minecraft gets away with somewhat - y'know, to a low-poly artist - shitty graphics because it's a good game," says Blanchard. "As much as I think Minecraft is overhyped and ridiculous, that game is fun, and that's why it made the money it did. I feel like as long as you know what you're doing and you're using low-poly as a tool to make your game better, it has a chance of taking off. But if people just start trying to do it because it's a trend, and they want to make money, it's gonna be terrible, and it's probably gonna make me switch to a totally different career path," he laughs.

"I hope more people pick [32-bit] up, because it's an awesome style."

In all seriousness, Blanchard welcomes more indie game artists to join him in revitalizing 32-bit graphics. "I hope more people pick it up, because it's an awesome style," says Blanchard. "I think if people keep at it, and get good enough and original enough, that would be pretty great. Every game I've ever played - including my own - with that art style, or something similar, is good." Having pretty much seen it all, Blanchard has just as much love for low-poly indies like The Amazing Frog and Strafe as studio-made outliers like Grow Home and Katamari Damacy.

And Blanchard isn't about to abandon the art style he worked so hard to perfect once Drift Stage is formally released. Right now, the team's considering the possibilities of making a low-poly mecha fighter in the same vein of the beloved Virtual On. Even as game graphics inch closer towards photorealism, the distinct 32-bit style holds an inherent appeal for Blanchard, who always seemed to be gaming one generation behind the curve (as evidenced by his devotion to the PlayStation 2 for years after the Xbox 360 and PS3 had launched). Recreating the low-poly aesthetic that Blanchard grew up with is something he does as much for himself as for anyone with fond memories of fifth-generation consoles. "There's gotta be more people like me out there," says Blanchard.

Lucas Sullivan is the former US Managing Editor of 12DOVE. Lucas spent seven years working for GR, starting as an Associate Editor in 2012 before climbing the ranks. He left us in 2019 to pursue a career path on the other side of the fence, joining 2K Games as a Global Content Manager. Lucas doesn't get to write about games like Borderlands and Mafia anymore, but he does get to help make and market them.