22 years. 3 developers. Only 2 games. The fascinating history of the Prey series

A story of lost portal guns (before Portal), Rogue One alumni, and the curse of Duke Nukem

Prey is out now on PS4, Xbox One and PC. That may sound like a simple, matter-of-fact statement, but it isn’t. This is only the second entry in a series that has spanned three decades, multiple developers and publishers, and many generations of gaming technology. The Prey franchise - originally conceived in 1995 - has managed to attract attention throughout its various development cycles, but in 22 years it has only managed to produce two, wildly different entries. The Prey you can play today has nothing in common with the original 2006 version, or the cancelled sequel (which in turn had little real relation to the original either). Confused? That’s where this feature comes in. To dig into the franchise's extraordinary history, I talked with various figures behind the original and the unreleased version of Prey 2. We discussed the initial development, the Human Head Studios' version that we actually got to play, and the problems and particulars that have been part of this sci-fi series’ 22-year development.

The beginning

While Prey was eventually released on Xbox 360 and PC in 2006, its roots extend much further back. What we eventually got was a first-person story of one man - Tommy - fighting aliens on board their ship after they kidnapped his girlfriend. It has all kinds of nifty portal tech and gravity defying gameplay, mixed in with some truly horrific creatures to kill. Overall, it's a damn good game, and was one of the early highlights of the Xbox 360's life. Development on the initial version of Prey, though, started in the mid-’90s, following 3D Realms’ Rise of the Triad. Back then, creation of the game wasn't expected to take longer than two or three years. It wasn't just Prey being built, though: 3D Realms was also making a full 3D engine to run it, and after several years of development, Prey would fall to the wayside as the company's focus shifted to a different project.

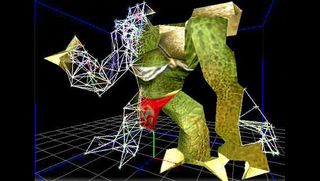

Development began in 1995. By around the middle of 1996, Prey had made progress. "In basically, I think, June, May/June of ‘96, we had a functioning prototype that was playable," says Mark Dochtermann, former lead programmer, 3D Realms. Some parts of the game weren't proven yet, but there was a light at the end of the tunnel. "Our technology was coming along," he continues. "You could see a path where it was going to be fast enough to use".

And while the team had ambitious goals, Dochtermann was "really proud" of what they were able to put together. "We had all of the elements of an engine to start actually building an experience... it was an insanely difficult technical feat to pull off". The problem, as Dochtermann tells it, came from 3D Realms' George Broussard - coincidentally the man who oversaw development of Duke Nukem Forever for 12 years. According to Dochtermann, Broussard told him that the team somewhat had Broussard's trust, but he was going to get involved and change things toward the end of development regardless.

"This is not meant to be like, you know, George is a bad person," Dochtermann says. "But that is the way that he approached product design. He was definitely more of a tweaker". Dochtermann didn't think Broussard's approach would work for Prey, and that the project needed long-term planning. "I realized that this project was never going to get finished at 3D Realms," Dochtermann says. He eventually left the development studio in August 1996.

Dochtermann wasn't the only person to leave, however, and after a staff exodus in 1996, Prey’s former producer/designer at 3D Realms, Paul Schuytema, was brought in. "The first steps were getting the core engine components in place, designing a level editor and getting an over-arching design and story for the game," Schuytema says.

Duking it out with other games

Another change for Prey was on the horizon. According to Scott Miller, founder/owner/CCO of 3D Realms, Prey's deprioritisation in 1998 was because of another infamous game the team was working on: Duke Nukem Forever. "It really came down to this," Miller says. "We had Duke Nukem Forever. And we had Prey. And it turned out that as a pretty small developer, this was more than we could chew."

Sign up to the 12DOVE Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

In a 1999 post on the company's site, it mentioned dissatisfaction with the ‘98 version of Prey's tech. And with the company's priority shifting to Duke, much of the Prey team was moved to that project instead. That doesn’t mean it was completely abandoned, however. In 1998, following the shift to Duke, 3D Realms added Corrinne Yu to do engine work for Prey. But the company’s focus was on Duke Nukem.

What did Prey look like before the company’s shift to Duke? "Our in-house tools [at 3D Realms] were just amazing - the level editor and script environment really made you feel like you were sculpting a real world out of the dark void of cyberspace," Schuytema says. "The editor was in-engine and it was just so damn immersive!" But a problem with tech was about to hurt development, according to Schytema.

Timing and industry changes turned to trouble for Prey. It was mostly developed on the 3DFX card and the Glide API ("It was the hot shit API of the day," Schuytema says) but internal troubles at 3DFX hit just as the Prey team was ready to go all-in with Glide. Meanwhile, Microsoft was getting its Direct X API off the ground. The team moved away from Glide, and ended up going with Direct X instead.

"It was the right call, but boy did it cost us," Schuytema says. "That was when William Scarboro (Head Engineer) had to essentially rebuild the engine, so it was non or semi-functional for a long time. There was just too much work to do and at that time, it was essentially only William working on the engine code". Schuytema very much credits the death of the first version of Prey to the stalled progress of the Direct X switch. And in 1998, George and Scott "pulled the plug," according to Schuytema. "It was a painful decision, but they had to make it". Schuytema left in 1998 too, and Prey sat unfinished and unreleased. "When I left, the game looked sort of like a Lamborghini that was getting its engine rebuilt - it was gorgeous and amazing, but it had parts all over the place!," Schuytema says.

Prey wouldn't get its solid breath of wind until 2001. Take-Two was flirting with the idea of reviving the game, and came to 3D Realms, who was still working on Duke Nukem Forever. It was decided that a change of creator was required to get Prey ready for release, so Human Head Studios was given the project, with 3D Realms providing some funding and being involved in "all aspects of design".

For this version, original features like portals and the Native American protagonist were kept, and it was also decided to make game's Cherokee mythology an important part of Prey. Miller recalls buying several books and lapping them up. No longer using the in-house work of the previous Prey versions, Human Head instead used the id Tech 4 engine, then being used to power the blisteringly impressive Quake 4 and Doom 3. More improvements were made along the way. "A lot of the stuff that's in Prey wasn't originally doable on the id engine," Miller says.

A new hope?

The writing process wasn't going well either, and Gary Whitta was brought in to pen the script. Wondering why you’ve heard of him? Whitta wrote Prey's script, and years later he worked on the story for a certain spin-off film for the Star Wars franchise: Rogue One: A Star Wars Story. In the earlier, 1996 version, the team had been taking influence from another, probably unexpected, science-fiction source: L. Ron Hubbard's Battlefield Earth: A Saga of the Year 3000.

"We wanted to have a game that had a strong sci-fi element, you know, carved out a different aspect of sci-fi that people hadn't seen before. That was obviously a challenge to figure out what we wanted that to be," says Chris Rhinehart, project lead on Prey 1 and 2 at Human Head Studios. "We wanted a non-conventional protagonist, we didn't want just another dude, you know, another bald white dude essentially."

The Native American protagonist, kept all the way from the initial version of Prey, was still going to be used. But he wasn’t intended as a lazy insertion, used simply for the sake of difference. "We also wanted something that was true to Native American mythology, history, and culture, something that didn't seem like it would be just a horrible stereotype," Rhinehart says.

One of Prey’s concepts even came from past projects that Human Head had worked on. The idea of wall-walk boots originally came up during initial work the studio did for Daikatana 2. That game never happened, and after that, Human Head started talking to Epic about handling Unreal 2. One of its ideas for that project: yup, those wall-walk boots. Human Head didn't end up doing Unreal 2 either, which was Prey’s gain. "Fast forward to Prey, we were like 'Alright, we would love to be able to do wall-walk boots,'" Rhinehart says. "So I'm glad that we finally managed to get that particular tech in the game."

Development for Prey wasn't all portals and roses, even at Human Head. Problems arose between 3D Realms and Take-Two. At one point during development, according to Miller, Take-Two actually stopped funding Prey over design disagreements, which including the publisher wanting to make it more like Nintendo’s Metroid. 3D Realms picked up the monetary slack as Human Head continued development. Bridges were rebuilt, and Take-Two ultimately started the cash flow again. It didn't, however, give Human Head as much time as Miller thought it needed.

"I felt like the game needed another four to six months," Miller says. "Because there was some key things that weren't in the game that I really felt were important. And one of those key things was putting back in that portal gun." That was a tough break for the development team. Prey had been in development for more than ten years at this point, and some features had to be compromised on. "It was just... a crying shame that we didn't have that portal gun in there, because, you know, a year or two later the game Portal comes out, and... steals our thunder in that area," Miller added.

Lightning strikes twice - the sequel that never was

After roughly 11 years of ideas, delays, frustrations, and resolutions, Prey finally came out in 2006 to generally positive critical reception. Despite the frustrating development history of the original, initial work for Prey 2 had already begun. "We had some killer directions to take portals, that no game has yet done," Miller says. "And those ideas are still waiting to be done".

Another issue arose, however. Take-Two wasn't game for a sequel. But despite starting work on a different project and wanting to take a break from Prey, Human Head Studios was still working with 3D Realms on what a possible Prey 2 could look like. And after a pitch from Human Head, Bethesda picked up the rights for the series in 2009. This sequel was a radically different game: the portals, wall-walking boots, and Native Americans were gone. Instead you played as a human bounty hunter, deep in space, looking to solve mysteries by cover-shooting and chasing down alien scum using a slick free-running system reminiscent of Mirror’s Edge. Think Deus Ex meets Mass Effect meets Prince of Persia, and you’re getting close to what it might have been like. During closed demos of the game, the creators teased links to Tommy, the hero from the original Prey, but he was no longer the protagonist.

Human Head worked on the game with Bethesda until late 2011. At that point, it was possible to play through all of the game's major levels, many of the weapons were in, as were the enemies. "We were really proud and happy with everything that we had created at that point," Rhinehart says. And while the first pitch for Prey 2 did include Tommy, Human Head instead decided to take the sequel in a different direction, while still working inside the universe of the first Prey game.

"If Prey 1 was Luke's story from Star Wars, Prey 2 was Boba Fett's story," Rhinehart says. But, Human Head's version of Prey 2 - much like the misbegotten original version of Prey - would never see release. Bethesda officially announced its cancellation in 2014, before revealing Arkane Studio's rebooted version of Prey in 2016. "It's a pity that we didn't get to finish that game... to this day I'm not exactly sure what happened between Bethesda and Human Head," Miller says.

Rhinehart sees a more darkly funny side to things, saying: "It would be funny if... this Prey franchise was essentially a franchise where a new developer takes it and releases a brand new Prey every five to 10 years". After 22 years and only two games, that certainly doesn’t seem an impossible whimsy. Make no mistake though, the new Prey - which is again, little to do with either the original game or the cancelled sequel - is a damn entertaining experience. And if this current version sells well enough, a potential Prey 2 (which will actually be Prey 3, but let’s not confuse things too much) can break the curse and give this franchise some stability. Or maybe Rhinehart’s prediction will come true, and it will be some time - and another developer - before fans see Prey again. Time will tell.

Article note: When approached to be included in this article, a Bethesda PR rep said the company has said all it has to say about Prey 2’s development.

Willie was once a writer and editor covering music and games. He is now the web content manager at Niantic for Pokemon Go. Willie is also a barrel-rider, Reliable Brave Guy (TM), and podcast host at 8 Bit Awesome.

Death Stranding 2 draws ever closer as Hideo Kojima shares emotional behind-the-scenes update from "important scene" that wrapped recording for 6 voice actors at once

Cancelled The Last of Us Online game was "great," but former PlayStation exec says Naughty Dog had to scrap it after Bungie told them how much work it would be

Most Popular