Why you can trust 12DOVE

Given that Danny Boyle doesn’t so much direct films as energise them in kinetic flurries, what drew him to the true tale of a man trapped in one spot for five days?

While cavalier ‘canyoneer’ Aron Ralston’s 2003 nightmare pivoted on paralysis, Boyle’s pictures major in motion, be it Trainspotting’s chemical come-on or the pell-mell picaresque of Slumdog Millionaire.

However, by immobilising himself, Boyle cuts fast and direct to a theme his films thrive on: lust for life under straitened circumstances.

Which is to say, in part, that advance scare-mongering isn’t to be trusted. Tales of viewers fainting followed festival previews, apparently cold-cocked by what Ralston did (clue: cheap knife) to escape from the dislodged boulder pinning him down.

But as grim as that scene is, it’s only one necessary part of a film that otherwise brims with life-boosting feeling, a movie that finds joy in a tale of extreme on-the-spot surgery without becoming bogus.

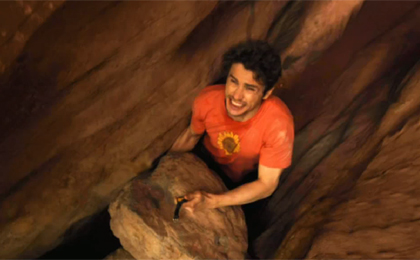

As Ralston hits Utah’s Blue John Canyon for thrills, the opening erupts in a pace-setting flush of split-screen action, giddy jump-cuts and maxed music. Ralston’s arrogance isn’t softened: played to the hilt by James Franco, he’s part narcissist, part nutjob, taking pics of himself and taking off to deadly terrain without telling anyone where he’s going.

We’re buzzing with this madman until he slips and... gets stuck, as his book title puts it, Between A Rock And A Hard Place. The viewer endurance test should start here, but the filmmaking transfixes.

Ralston’s thoughts and feelings are exposed in mash-ups of montage and split-screen, flashbacks and fantasies, aided by dazzling tag-team cinematography from Anthony Dod Mantle and Enrique Chediak.

Franco’s delivery is equally quicksilver, cocky then panicky then furious then heartbreaking as Aron’s options dwindle with his water.

Granted, some of Boyle’s formal flourishes do distract. Over-eager pacing fudges a vital sense of despair-heightening duration. But at best, he illuminates Ralston’s interior brilliantly so as to stress the connections to other lives that drove him to do something unthinkable, a stress that turns near-mystical and terribly moving when one particular life enters the picture.

The infamously nasty scenes here get you in the gut, true. But as Boyle’s humanist thrust powers towards an ecstatic conclusion, it’s the emotional cuts that linger.

Kevin Harley is a freelance journalist with bylines at Total Film, Radio Times, The List, and others, specializing in film and music coverage. He can most commonly be found writing movie reviews and previews at 12DOVE.

Beloved Bethesda actor from Skyim, Fallout 3, and more shares heartfelt thanks after waking up from a coma and discovering hundreds of people have donated to his medical bills

Stranger Things season 5 releasing in 2025 might not be a certainty as its creators admit that target is "quite the push"

James Gunn weighs in on a potential deep-cut Avengers: Endgame and Guardians of the Galaxy plot hole